In literature and social media, the “sad girl” archetype has re-emerged as a prominent figure, blending emotional fragility with aesthetic allure. Its significant role in bringing popularity reflects a growing fascination with performative vulnerability. For teenage girls like me, the archetype offers a space to reflect, live vicariously through the characters, and process complex emotions.

Here is a curated list of four works that explore girlhood and sadness as an experience and helps explain why this genre resonates among teenage girls:

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

On a “quiet and sultry” summer, Esther Greenwood, a young woman with dreams of becoming a poet, embarks on a whirlwind internship at a fashion magazine. Set in 1950s New York City, the novel follows her slow unraveling as she returns to her mother’s home and falls into a deep depression after facing rejection and disillusionment.

Nylon describes The Bell Jar as a “rite of passage for disillusioned girls,” highlighting how Esther internalizes societal expectations while silently bearing their weight. Plath doesn’t glamorize sadness–she presents it as the inevitable result of a world that refuses to embrace female complexity.

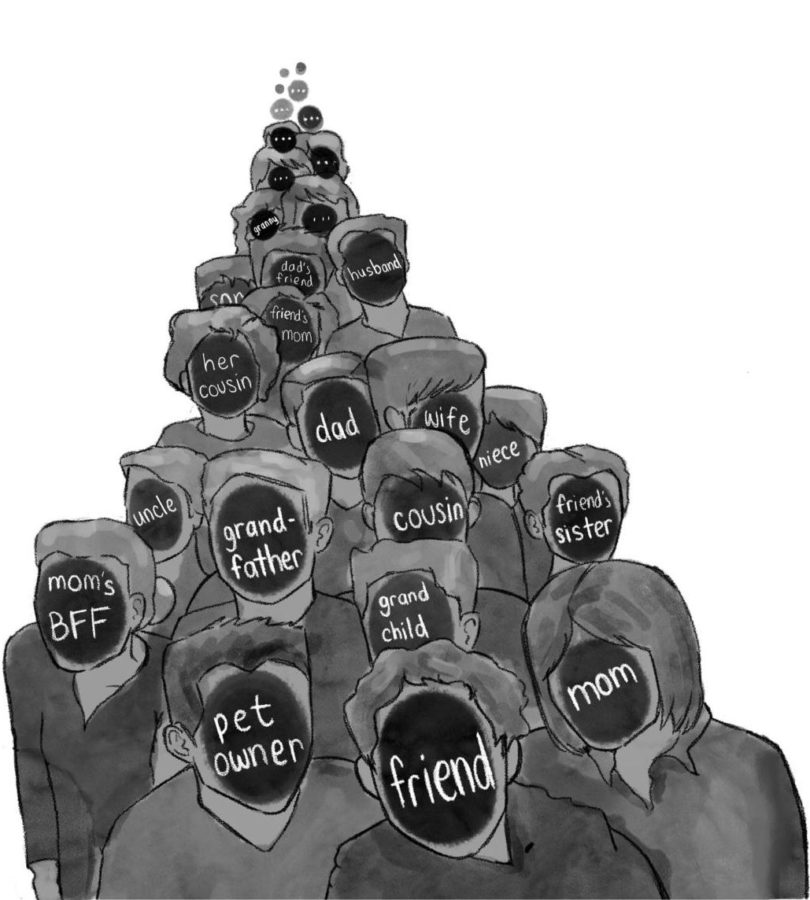

Esther describes her life as a fig tree, with each branch symbolizing a different future: writer, traveler, mother. She’s paralyzed by the pressure to choose just one, knowing that picking one means losing the rest. This metaphor captures what many teens face: every choice, especially about our future, feels set in stone. Furthermore, Plath’s analogy resonates with students struggling with indecision, perfectionism, and the fear of missing out on the “right” path.

Esther’s alienation and mental health struggles reflect broader discomfort with women’s emotional expression. Her depression is not weakness—it is a response to the impossible pressure to be exceptional, beautiful, and composed. This pressure pushes young women to conform to an idealized version of femininity that limits them from thriving in a demanding society.

Many teenagers know the pressure of that dreaded question at family gatherings: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” It sounds simple, but for some of us, it sparks anxiety. Why choose one thing when we’re expected to be good at everything? That pressure to be ambitious, passionate, and put-together lingers, quietly shaping how we view success and self-worth. Esther’s fear of choosing the wrong decision reflects a feeling many of us carry without realizing it.

In conclusion, The Bell Jar resonates with readers drawn to introspective stories that confront the emotional toll of societal expectations. For many, it becomes a mirror of their internal conflicts—a story that makes them feel seen in a world that often silences them.

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides (1993)

Set in the 1970s, Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides tells the haunting story of five Lisbon sisters growing up in a quiet suburb near Detroit. Seen through the eyes of the neighborhood boys, the sisters become a symbol of longing, mystery, and misunderstood girlhood.

The novel captures the isolation, repression, and romanticized tragedy imposed on the girls by their parents and society. Eugneides uses the suburban backdrop to explore themes of identity, freedom, and the limits placed on young teenagers’ lives.

Obsessively narrating the sister’s life from a distance, the novel exposes how society romanticizes female suffering, turning real emotional pain into mystery and myth. For teenage girls, this portrayal reflects how their struggles are often minimized or aestheticized.

Eugenides’s vivid descriptions and symbolic use of setting and time create a dreamlike world that resonates with young readers navigating similar emotional terrains. His storytelling reminds us how quickly girlhood can be shaped—and sometimes controlled—by external narratives.

Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson (1999)

Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak follows Mellinda Sordino, a high school freshman who becomes selectively mute after a traumatic sexual assault. Shunned by her peers and misunderstood by adults, Melinda retreats into silence until she begins to express herself through art. This creative outlet becomes her way of processing pain and reclaiming her voice.

In a diary-like, first-person narrative, Speak invites teenage readers to step into Melinda’s quiet world. Her raw, honest voice captures the isolation and confusion many girls feel but rarely express. The high school setting—with cruel whispers, indifferent teachers, and cliques—feels painfully honest and familiar.

The novel shows how one traumatic event can define a person’s identity in the eyes of others, even when they don’t know the whole truth. Anderson portrays the emotional aftermath of assault with sensitivity and depth, revealing how silence can serve as both a survival mechanism and a source of power.

When I first moved to this school, we read Speak in English class. Since it was a short story, I finished it in one sitting. Despite this, it was a powerful story—the kind that lingers in my mind. It reminded me of what it’s like to walk through hallways feeling invisible, to second-guess every glance or laugh. To every girl who ever felt small, Speak offers something rare: a quiet validation.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (2018)

Set in early 2000s New York, Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel delves into the life of an unnamed narrator living in New York City who decides to sleep for an entire year using a cocktail of prescription drugs after being fired from her art gallery job. Her goal is to escape grief, numbness, and the pressures of reality.

Written in a first-person perspective, the narrator is tragic and flawed, but not weak. Moshfegh shows that even a privileged, attractive woman can still be deeply affected by pain, loss, and trauma. Her struggles stem from an emotionally neglectful childhood and a complicated relationship with her late mother.

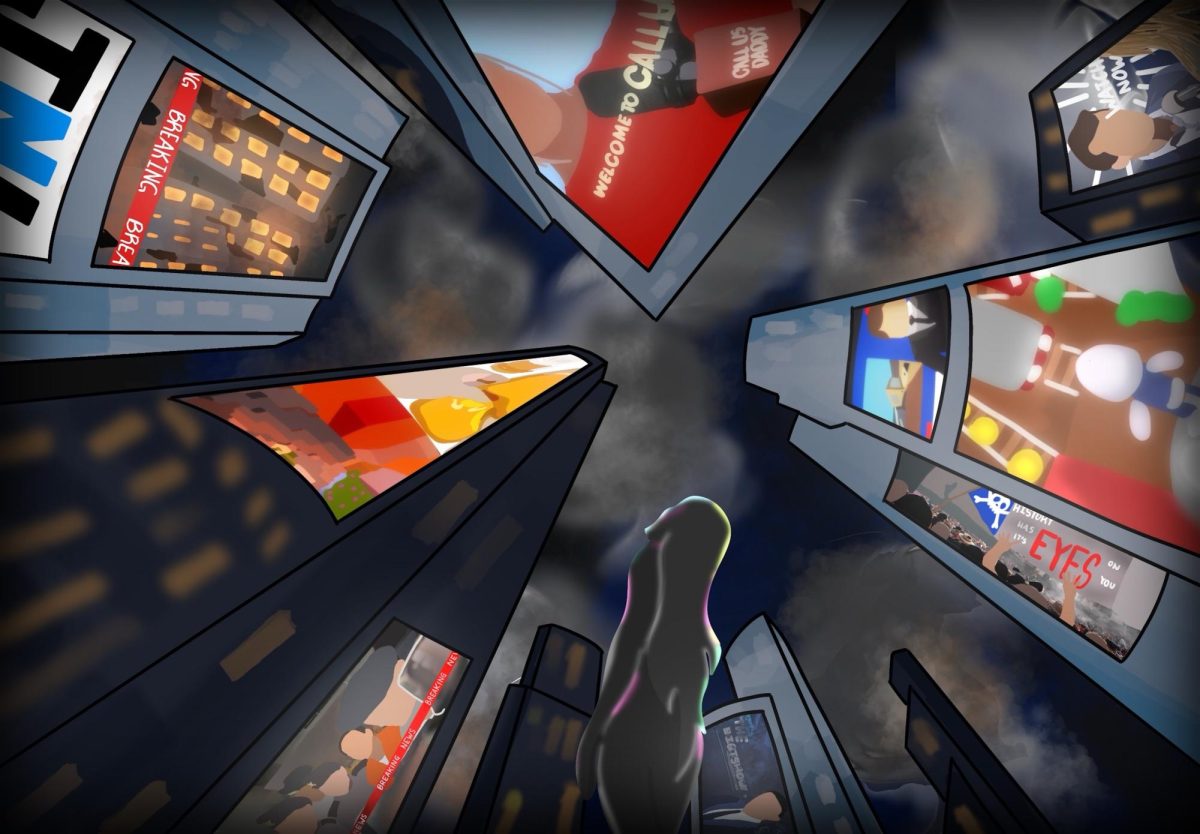

Sleep becomes a form of self-preservation—a way to shield herself from the expectations and emptiness of modern life. For readers, her stillness is not just physical but symbolic: a rejection of the demand to constantly perform or produce.

For many of us, balancing social expectations and emotional stress makes the potrayal of sleep depreviation deeply relatable. Like Mosfegh’s narrator, they may crave stillness to pause, disconnect, and temporarily escape from the lives that demand constant output. In this sense, sleep becomes an act of quiet rebellion and a rare moment of control.

Through the “sad girl” archetype, these three authors shed light on the emotional lives of young women’s power. It showcases their vulnerability, anger, grief, and quiet strength. Each author uses a distinctive style to explore how girlhood is shaped by societal pressures, internal conflict, and the search for meaning. Ultimately, this genre validates feelings that are often dismissed.