Journalism is meant to act as the Fourth Estate that keeps power in check, exposes injustice, and amplifies the voices of the voiceless. Its core responsibility is to serve the public, not the powerful. However, the line between objective reporting and biased coverage has become increasingly blurred. Many media outlets now operate within environments shaped by political pressure, corporate interests, and algorithm-driven engagement—all of which influence how stories are selected, framed, and told.

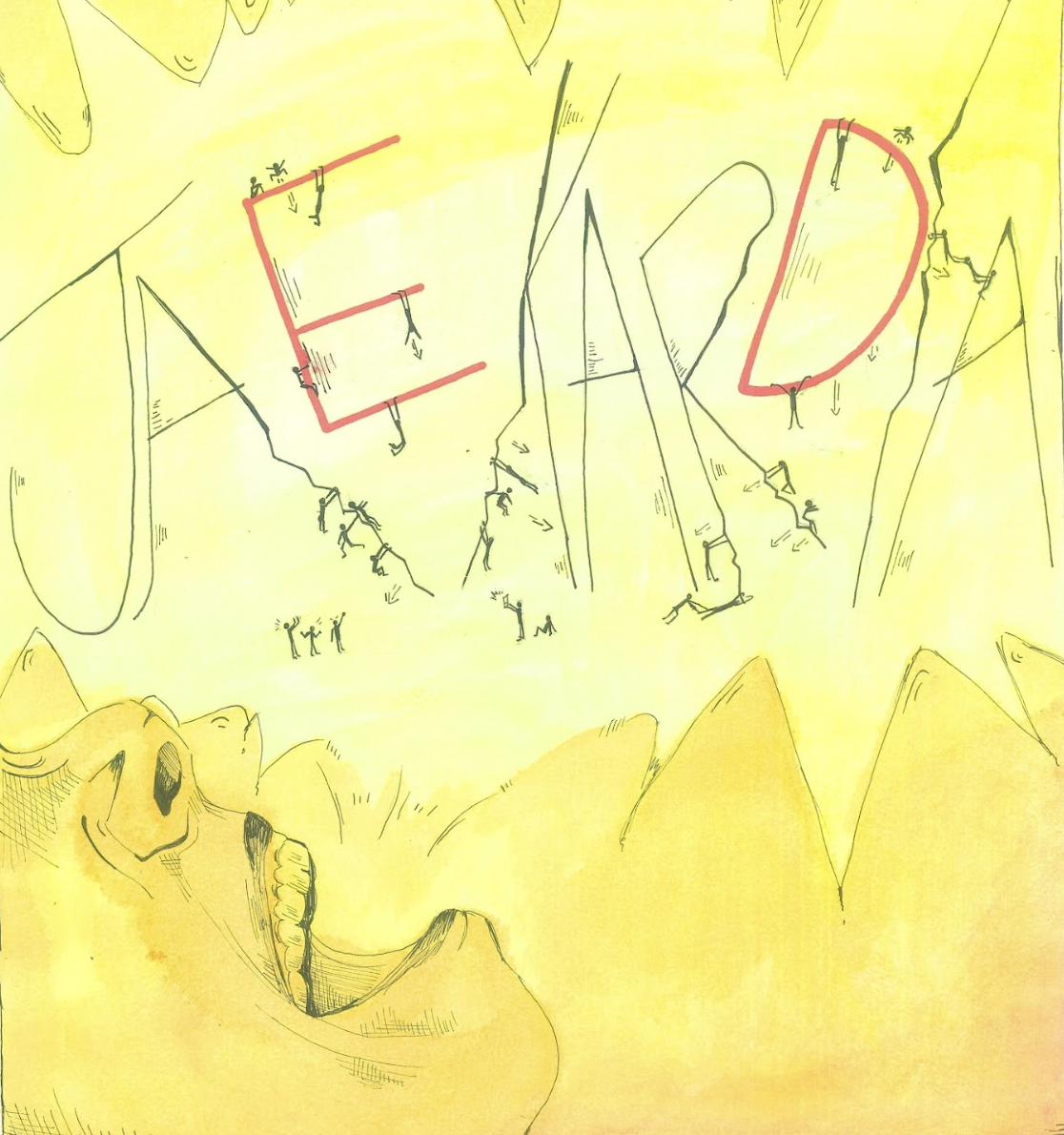

Amid these shifting influences, it is important to distinguish between two fundamentally different approaches to journalism: watchdog and guard-dog journalism. Watchdog journalism holds those in power, governments, corporations, and institutions accountable. It exposes wrongdoing, promotes transparency, and safeguards public interest. In contrast, guard-dog journalism reinforces dominant narratives and protects elite interests. Instead of scrutinizing authority, it often downplays criticism and frames events in ways that preserve existing power structures.

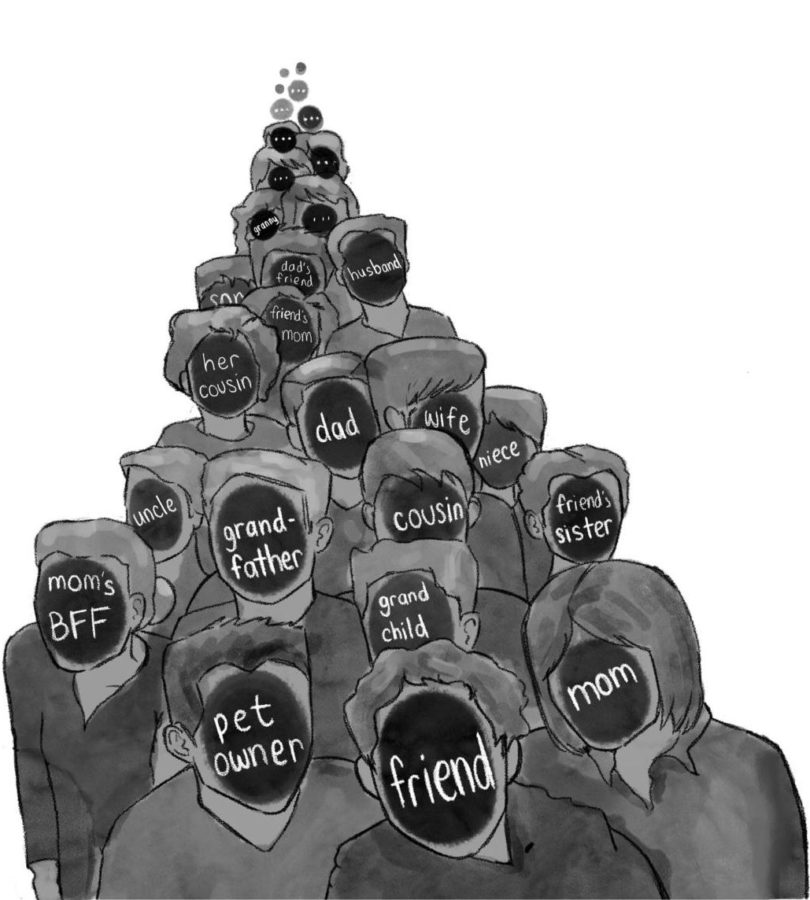

When journalism strays from objectivity and reinforces bias, it distorts public understanding and deepens societal inequality. Marginalized communities are excluded from positions of influence and misrepresented in the narratives that shape public opinion. By failing to question its framing, the media risks becoming complicit in sustaining the injustices it claims to expose.

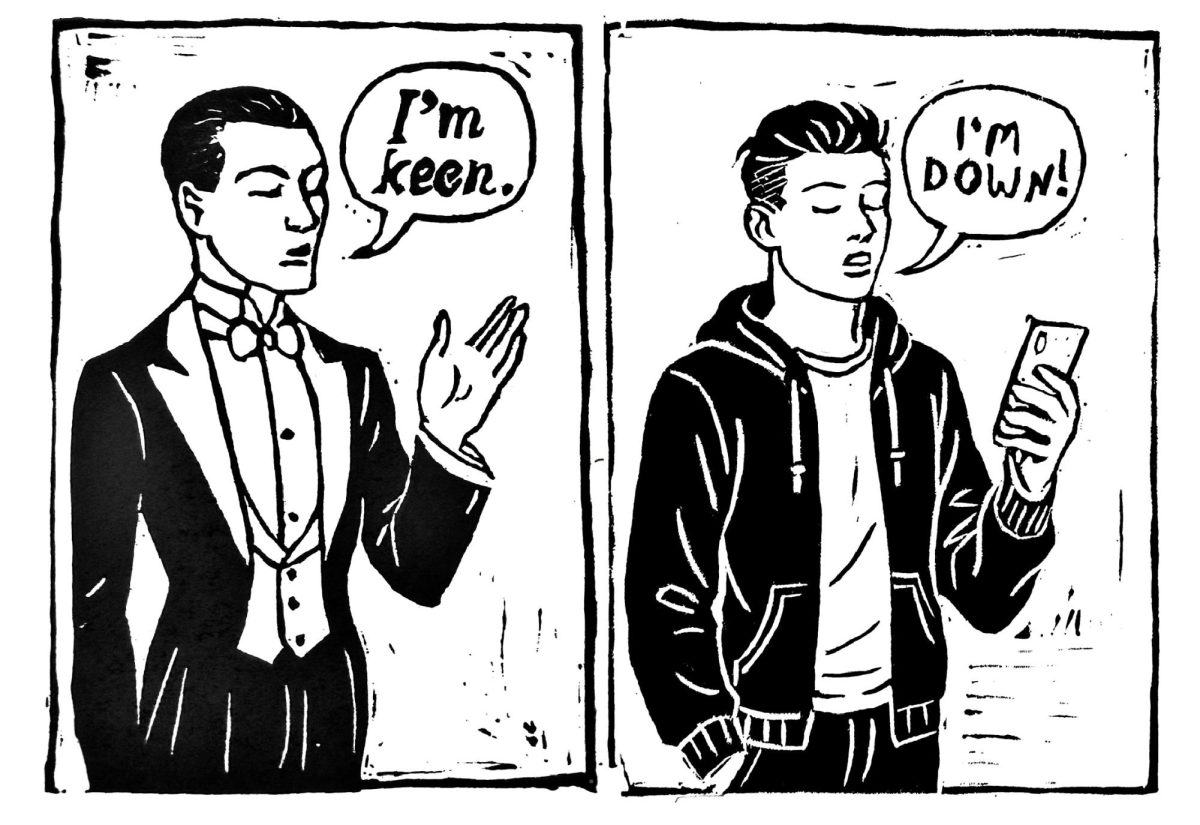

Media framing influences not only how we interpret events but also shapes who is perceived as credible or worthy of being heard. This becomes especially evident when individuals advocating for the exact cause are treated differently based on age, gender, or persona.

A striking example is Greta Thunberg, the teenage climate activist who quickly gained global attention, but not always in a respectful light. While her speeches and critiques of world leaders have earned praise from prominent figures, they have also provoked intense backlash. Unlike her older, often male counterparts who issue similar warnings, Thunberg is frequently dismissed, not for the substance of her message, but for how she delivers it. She is often labeled as “overly emotional,” “angry,” or “naive.”

After her “How Dare You” speech at the United Nations, commentators ridiculed her as a hysterical child and a brat chasing unrealistic dreams. By shifting the focus away from her message and magnifying her tone, critics sought to delegitimize her concerns, implying that climate change isn’t urgent because the messenger appears too emotional.

These responses reflect deeply ingrained sexist and ageist tropes that undermine her credibility and, by extension, the legitimacy of the climate movement.

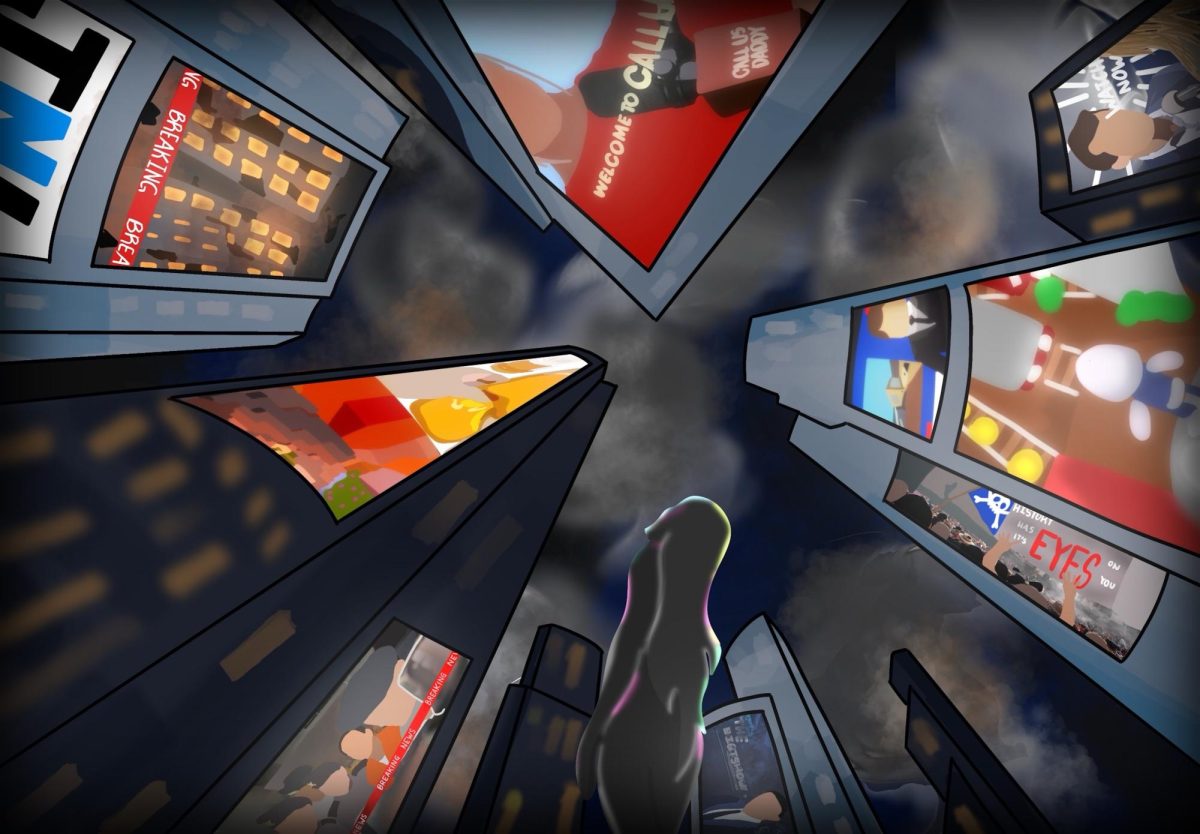

Additionally, the media’s portrayal of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement versus events like the January 6th Capitol insurrection starkly reveals how framing can alter public perception. Despite BLM being a decentralized, grassroots movement advocating for racial justice and police accountability, coverage often centered on terms like “looting,” “violence,” and “chaos.” Images of burning cars and shattered windows dominated headlines, while peaceful marches, community organizing, and the movement’s core messages were pushed to the margins.

In contrast, early reports of the January 6th insurrection, where rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to overturn a democratic election, were initially labeled by some outlets as a “protest” or “rally gone wrong.” The use of passive language, such as “clashes,” “tensions,” and “unrest,” subtly downplayed the gravity of the attack and the intentions behind it. This discrepancy in terminology—“riots” versus “protests”—is not accidental. It reflects underlying racial, political, and ideological biases that shape who is seen as a threat and who is given the benefit of the doubt.

Studies show that when movements such as BLM are associated with violence, regardless of whether participants or outside agitators committed the violence, public support declines. Meanwhile, white-led demonstrations—even those involving violence—are more likely to be interpreted as isolated incidents or expressions of frustration. The media’s responsibility in such cases isn’t just about reporting what happened—it’s about being conscious of how their language can uphold justice or perpetuate systemic inequality.

Just as individuals and movements are subject to selective framing, so too are entire nations—particularly when they exist outside the West’s sphere of cultural familiarity. The same disparity in emotional tone and public sympathy that affects protestors and activists also shows up in how the media reports global tragedies. Nowhere is this more visible than in the aftermath of natural disasters, where the identity of the country affected—its wealth, geography, and even perceived proximity to Western audiences—can dramatically influence both how much is reported and how personal that suffering is portrayed.

However, the implicit bias may be more challenging to realize due to the disparity in media coverage between a calamity in a less economically developed country (LEDC) and one in a more economically developed country (MEDC), which are typically also considered wealthier Western nations.

This distinction doesn’t always reveal itself through outright exclusion, but rather through subtle differences in tone and framing—particularly in how the media chooses to narrate suffering across global divides.

Consider how news outlets often report on earthquakes, hurricanes, or floods in LEDCs of the southern hemisphere: the language tends to revolve around statistics—death tolls, number of displaced individuals, hectares of land destroyed. Victims are frequently bound together as faceless masses: “thousands are left homeless,” “villagers stranded,” “death numbers have risen.” The narrative zooms out, emphasizing scale, destruction, and often chaos.

In contrast, when disasters hit an MEDC, typically in the northern hemisphere, the media zooms in on individual stories. We learn names, see close-up photos of grieving families, and hear heroic accounts of rescuers. In this case, the personal lives take center stage instead of the numbers.

A fair critique of this observation might argue that English-language media outlets are more inclined to focus on events within their geographic or linguistic sphere. From this perspective, the disparity could be attributed to proximity or audience relevance, rather than a deliberate marginalization of global suffering.

While there is some truth to these claims in that newsrooms prioritize domestic relevance, it does not fully explain the marked differences in tone, depth, and emotional framing or why international news outlets mimic the same pattern. The situation in MEDCs are humanized while situations in LEDCs are quantified. This distinction reflects the media bias that subtly implies certain lives are more relatable, deserving of empathy, and thus ultimately more newsworthy.

It is not that the disasters in the global south are not reported with no human elements at all, since there are definitely compassionate journalists telling those stories. Yet overall, there is a notable imbalance in focus and thus a lack of action from outside individuals or governments.

One comparison is the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2005 earthquake in Kashmir. The tsunami, which also affected many Western tourists vacationing in the affected country of Thailand, received enormous media attention and an outpouring of aid.

According to The Guardian, the UK raised a record £392 million. By contrast, the Kashmir quake just months later, which also killed tens of thousands, “received little coverage, money or sympathy” in Western media. These patterns show how specific framings of tragedy in Western media reinforce unequal hierarchies of empathy, privileging familiar lives while psychologically leaving distant suffering abstract and often unseen.

The way Western media frames international suffering does not exist in a vacuum—it is shaped by larger structural forces. These biases are not only a reflection of editorial choices or cultural distance, but also of how free the press is to operate in each country, and what institutional pressures shape those narratives. Whether by censorship, ownership, or ideological alignment, press freedom plays a critical role in determining who tells the story—and whose stories are silenced altogether.

It is also key to acknowledge that while the press is ideally meant to operate freely and hold power accountable, freedom of the media varies drastically across countries, shaping how stories are told, who is silenced in the process, and even what the truth is. As of the 2014 report of the World Press Freedom Index, 128 out of 180 evaluated countries are ranked as having a problematic situation or lower, highlighting a constrained journalism environment where governments can manipulate, censor, or fully control media narratives.

Yet still, these framing disparities—whether person-to-person, group-to-group, or country-to-country—are not isolated media slip-ups. They reveal a pattern about whose voices are legitimized and whose experiences are flattened. For a generation raised on headlines, reels, and algorithms, understanding the power of media framing isn’t optional but instead essential. If journalism continues to reflect existing power structures without interrogation, it risks becoming less a pillar of democracy and instead more a mirror of inequality. As information serves as currency and narratives shape power, journalism is critical to inform and uphold the truth with integrity, objectivity, and accountability, ensuring the media amplifies the truth while giving voice to not just some, but to all communities. If we fail to question the stories we are told, we risk living in a world shaped not by truth, but by the comfort of those in power.