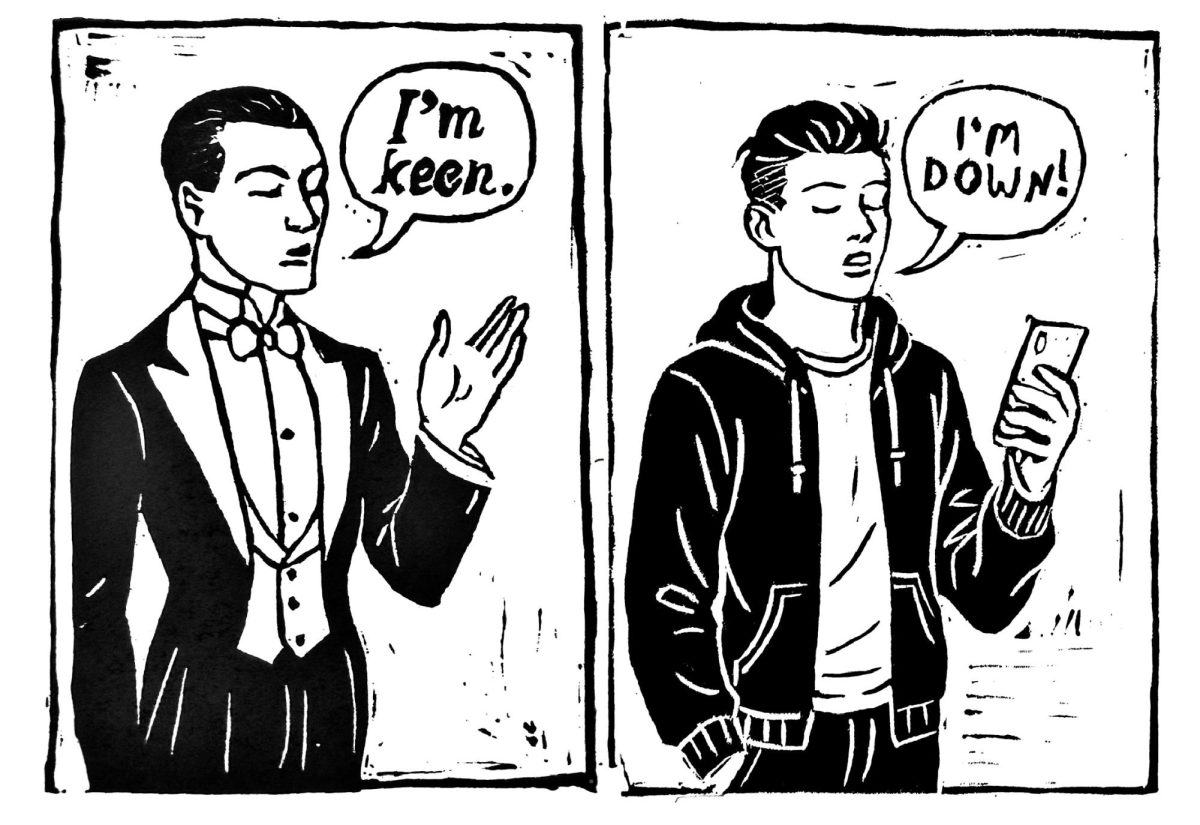

Viewers on social media platforms such as Tik-Tok and Instagram have recently witnessed a surge in content showcasing trends of “Girl Dinner,” “Girl Math,” and “Girl Hobbies.” The frequent use of the term “girl” in these phrases has begun to perpetuate demeaning stereotypes about women, despite the creators’ intentions of building community and driving conversation.

The hashtag “Girl Dinner,” with nearly 250,000 videos, features users showcasing their dinners, ranging from peanut butter with celery, to a Swiss cheese fondue, and sometimes even nothing at all. While the intention was to foster unity through sharing an absurd snack combo or a nostalgic childhood treat, many of these meals lack nutritional value. Utilizing “girl” to label an unhealthy meal, transforms the word into an adjective, describing the transition from a balanced dinner into a plate of mismatched bites.

Instead of referring to such meals as a “Girl Dinner,” calling them by their original name—a snack plate, smorgasbord, meze, or charcuterie board—can help avoid reinforcing negative stereotypes about the capability of girls. Snack plates have been eaten for centuries across various cultures without being gendered. Demonstrating this, sophomore Joljin V. noted that “[She] had participated in [“Girl Dinner”] way before it was even a trend.”

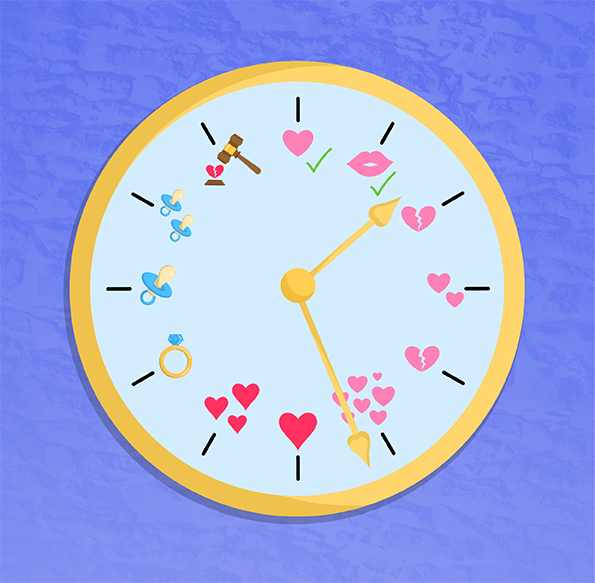

Similarly, the trend “Girl Math” sparked an explosive reaction, reaching users of all age groups and accumulating over 1 million interactions. “Girl Math” is the process of evaluating the worth of a purchase not by the price tag, but by the price per use and sentimental value. However, this practice can often be utilized to alleviate guilt or justify overconsumption. Framing this as a practice exclusive to females illustrates a limiting picture of female competence.

The term shifts the focus from accurate mathematics to subjective value; “girl” describes the movement from accuracy to unreliability. In this portrayal, the term perpetuates the stereotype that girls are incapable of making rational decisions and managing their finances—connecting to a larger narrative of female capabilities, one where they only

care about themselves. The issue is not viewing purchases from a different angle; it is labeling inherently flawed techniques as a female in nature, which retrogresses the perspective of female mathematic ability.

The third trend, “Girl Hobbies,” addresses the shame of not possessing “typical” hobbies such as sports, reading, or the arts by redefining everyday tasks as hobbies. They do not eat—they “get a sweet treat”—and they do not sleep—they “Girl Nap.” However, the trend immediately faced backlash due to its limiting rhetoric. Social Studies teacher Ms. Krouse, remarked, “It seems reductive to reduce your hobbies to treating yourself.” By making these habits seem as if they are exclusive to girls, we are describing female capability to such a finite extent.

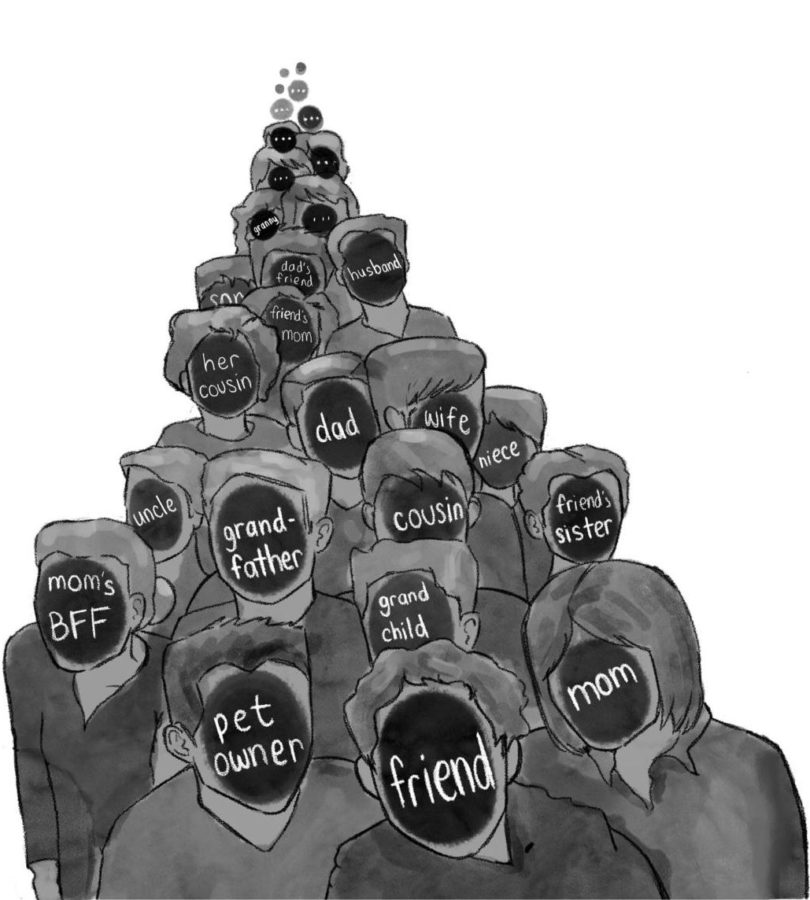

These trends have created ostracising consequences instead of unifying solutions. What makes these infantilizing phrases different from the more common expressions of patronization is that they are coined by women and consumed by a predominantly female audience, creating heavily divisive consequences.

Ms. Krouse emphasizes the critical importance of actively assessing the content we consume on social media in order to discern and challenge the underlying messages being conveyed. She noted, “It is open for people to justify discrimination based on the belief that women cannot do math the ‘right’ way.” Therefore, it is crucial we challenge these oppressive narratives instead of entertaining and perpetuating them.

At this point, who needs men for misogyny when we are doing it to ourselves?