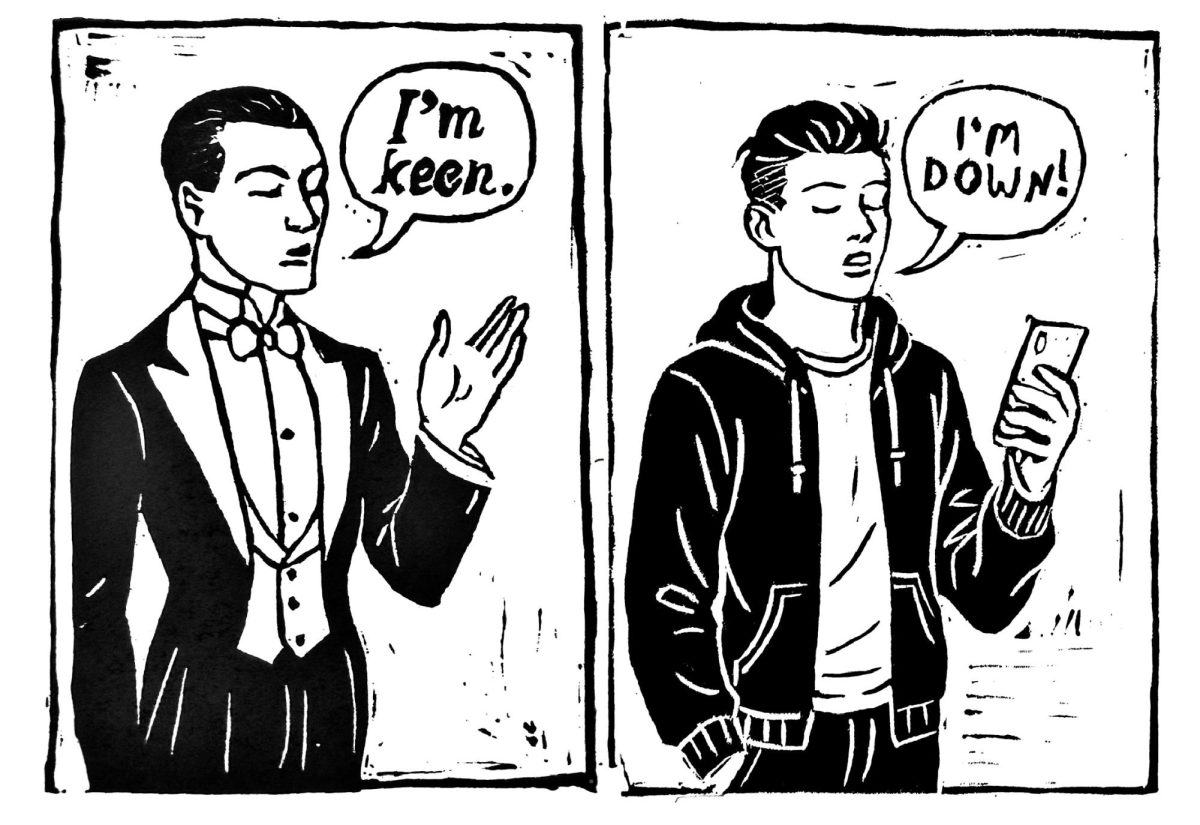

Mental health struggles, once considered taboo, have become more socially accepted with each passing year. Today, phrases such as “my therapist says that” — would not incite a batted eye. Celebrating this newfound acceptance is important as more cultures progress the shame that lingers from generations past. Still, in some aspects, we have overcompensated to the point that openness and the mundanely regular nature of the subject trumps privacy.

It is important to applaud the progress we have made as a society regarding the acceptance of unstable mental health. These conversations can be life-saving, and I endorse the continued embrace of therapy, self-improvement, and seeking help. Where my issue lies is the unintended and widely undiscussed consequences of the movement for increased mental health awareness, from needless visibility that sets sick people up for failure to the broadened requirements for diagnoses that those with milder experiences may stick to.

Mental health is important to any student’s mental stability and JIS aware of that. The school offers in-house therapy, coping strategies, and a remarkable counseling department that is able and willing to help students navigate the inevitable hardships of adolescence. Initiatives such as SLA lessons and wellbeing surveys help the school identify students who are genuinely in need — and looking for help.

As students, teachers, and parents are exposed to more conversations surrounding mental health, whether in school or not, internal dialogue, once tinted with shame and isolation, is now out in the open. Because as we share our experiences, we find them to be shared experiences. While this sense of community can ease feelings of loneliness, it also encroaches on the privacy of one’s health.

While struggles with mental health are no longer considered taboo, society must remember that they are still personal. Just because talking about “it” is now socially acceptable does not mean “it” should be brought up if you see someone struggling. This is especially applicable if a person whom you do not know well is visibly struggling. Even if your intentions are genuine, your pity can be their poison.

According to a clinical psychologist at Illinois Institute of Technology, Adam Fominaya, pity can have consequences just as impactful as the resistance to mental health we have seen in years past and certain cultures today. Foyminaya acknowledges that while “pity [is expected to] lead to positive behavioral responses, the results of his study show that pity can also lead to negative self-effects that persist months later and lead to adverse clinical outcomes.” Such consequences include decreased self-esteem, increased feelings of hopelessness, and depression. While these outcomes may not be discussed, I know they are real.

Take my freshman year in high school as an example. I was going through a hard time, and my therapist suggested that I take a walk around my neighborhood every day. I hated it. I hated my neighbors. Their hand on their chest, the “how you doing champ?”; “I’m here if you ever need to talk”; or “have you tried a break from social media?” There is a fine line between pity and empathy. When the line is crossed, it makes the “survivor” feel less than human—swallowing their pride as you dish up unsolicited advice.

And so I walked away, and I walked home. As I did, I thought “I should take more deep breaths”, and “I could try weight lifting as the guy down the street told me,” and “Susan’s essential oils sounded promising.” When the breathing exercises didn’t help and I couldn’t work out, felt I was beyond repair. But worst of all, I felt so needlessly exposed. I had already sought out support from my loved ones. The people I wish refrained from reaching out were those I did not know well.

The climate of mental health awareness has made people of all ages and backgrounds increasingly okay with discussing “it” albeit some age groups and cultures more than others. And while, for the most part, these actions and little suggestions stem from innocent motivations, it makes those with visible poor mental health feel out in the open— publically failing to follow through and “fix it” with mindfulness, and two weeks of ineffective home workouts.

Furthermore, increased awareness goes beyond an influx of unnecessary personal attention to those who don’t want it. In fact, in a time where attention is a commodity, those who, for example, suffer from mild anxiety may find themselves identifying with more severe illnesses, intentionally or not. According to Oxford University psychologist Lucy Foulkes, the subconscious exaggeration of mental health symptoms in a person’s head, resulting from “excessive” conversations on the matter, can manifest as intensified actual symptoms as well, inciting worsened health for those with moderate mental stability as well as those with more severe conditions.

So, what should you do when someone you know is clearly struggling? Please consider the following before you intervene.

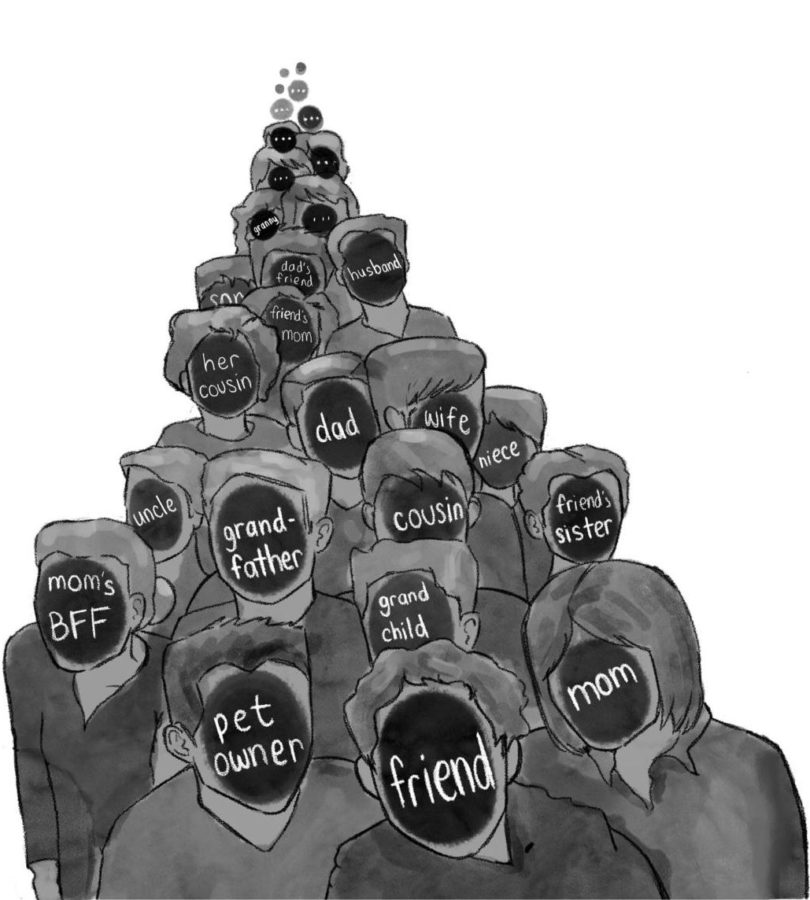

Firstly— and most importantly— how close are you to this individual? Are they your child, best friend, neighbor, or that kid you met once? Defining your relationship with this person is essential to understanding the boundaries you should and should not cross.

Secondly, ask yourself if reaching out is necessary. If this person is not incredibly close to you but you know they have no one else in their life, and they are in serious need of professional attention, consider reaching out to them or the JIS counseling staff, depending on the severity and context of the situation.

Still it is a relief that these struggles are no longer confined to our minds. It is nice to know that we are not alone as we navigate the inevitable challenges of the human experience, even at varying scales of intensity.

Yet, with everything out in the open, for better or worse, I hope we can one day find a balance between privacy and intervention. So, check in on your friends if you are close, and seek help from a professional if you need it. But maybe, just because we can talk about it, doesn’t mean we must.