For decades, women in horror films have been predominantly actresses cast as helpless victims. Female roles were confined to shrieking and fleeing from danger, their characters limited to nothing but the need for a damsel in distress—or a “scream queen,” as the term is now coined, their behaviors as helpless as their fates hopeless.

However, in the 1970s, there marked a turning point in the horror industry: women were now being represented as the Final Girl. Popularized by the films Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980), this new trope embodied a character who was not a passive victim, but rather a resilient and resourceful survivor. More often than not, she even outwitted and overcame the malicious forces that sought to eliminate her. For the first time, an archetype challenged the traditional gender roles within horror movies; however, this did not lead to an entire breakaway from traditional expectations.

Indeed, it is often thought that the survival of the Final Girl is due to her moral character over other survivors—morals that frequently stem from patriarchal and puritanical norms. She’s kinder or doesn’t drink or party. Not only that, but there’s also a lot to say about a girl’s journey to becoming a Final Girl: she must be put into violent and traumatic situations in order to come out on top. This new depiction of female characters brings with it its own problems.

“In horror, the Final Girl trope throws women a bone,” wrote Kelsey Christine McConnell for The Lineup. But really, if you take a look at the state of the world—especially when you start to consider the intersectionality of women so greatly underepresented in film—women face violence every day.”

In reality, many girls begin preparing for exclusionary behavior the moment they hit puberty, and sometimes even earlier. Women are constantly at risk from gender-based threats such as stalking, domestic abuse, and sexual assault. They frequently take up oppression head-on and fight back with everything they have.

“Painting the women who don’t happen to survive [violent encounters] as weak or less than a Final Girl is a pretty bad look,” McConnell continues.

Even though the Final Girl was a survivor—and marked a significant step forward in the horror genre—actresses were still mainly cast as victims. However, in the 1980s and 1990s, a new wave of horror films began in which the exploration of the complexity and depth of female villains ensued. For instance, the films Misery (1990) and Carrie (1976 and 2013) delved into the psychological aspects of broken yet empowered female characters, humanizing them despite their still horrifying acts.

This pattern continued in the early 2000s, when women began to make significant contributions to the horror industry. Actress Sarah Michelle Gellar embodied an independent female protagonist in The Grudge (2004), while Naomi Watts took on the role of an autonomous single mother in The Ring (2002).

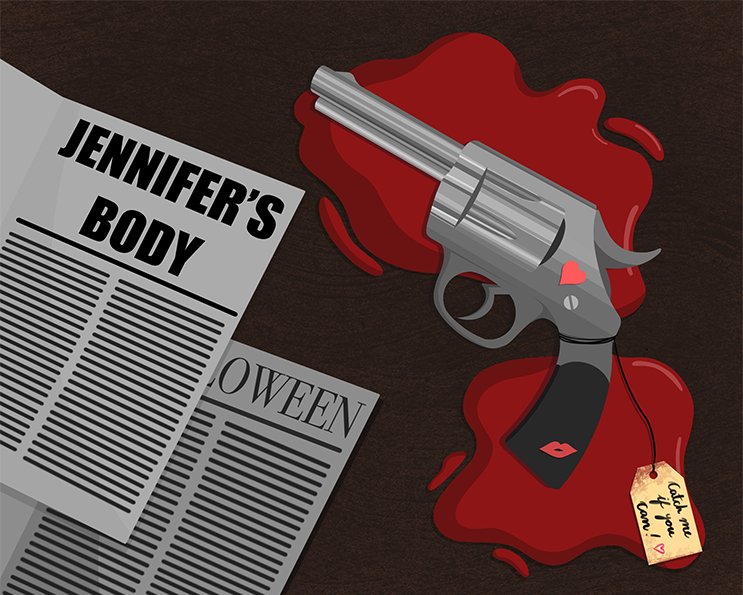

The same could be said for women behind the camera. Director and screenwriter Jennifer Kent led the production of The Babadook (2014), while screenwriter Karyn Kusama brought fresh perspectives to horror storytelling in Jennifer’s Body (2009). Through exploring the themes of trauma, motherhood, and identity, these works not only offered new narratives, but also contributed to the diversity and depth of female characters in the horror genre as a whole.

As we as a society continue to redefine our perception of gender roles, horror cinema, too, evolves with it. Within the development of female roles in horror movies, broader societal change is evident. As we look ahead, it is clear that the evolution of women in horror films is far from over, promising even more exciting and inclusive developments.