“Good Girl” versus “Bad Girl”

A dichotomy based on hypocrisy and misogyny.

Whether in action-packed franchises such as Indiana Jones, Spider-Man, and Mission Impossible, or in familiar love stories like Disney’s Cinderella, To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, or Bridgerton, “attractive” women traditionally fit into one of two tropes: the “good girl” or the “bad girl”. We enjoy these tropes in popular culture and our favorite films, present everywhere in mainstream media. However, these two archetypes, both individually and as a dichotomy, are responsible for more harm than we know.

A Lack of Autonomy

The “good girl” is kind, modest, and a dutiful daughter. She follows conventionally feminine traits and hobbies, and not-so-coincidentally, most of the time she’s white. But first and foremost, the “good girl” is a virgin. Her chastity and conscientiousness are an integral part of her personality, as well as her primary shortcoming.

Sandy, Grease, is one of many flawed renditions of said character trope. The protagonist’s aversion to explicit intimacy and rebellious activities makes her the object of her peers’ scrutiny. She is criticized for being “lousy with virginity,” made fun of for her relative lack of sexual experience. Her partner frequently victimizes himself when she rejects his sexual advances, and is even dedicated a scene about how the interaction “hurt [him] real bad.” Ultimately, this sends the message that peer conformity comes before one’s personal autonomy—an especially harmful consensus when in regard to a girl’s sexual boundaries.

The “good girl” is flawed as she is a prude, depicted as so uptight that she doesn’t know how to have fun.

However, is that really a flaw? Rather, it is the opposing mindset at fault. Peer pressure is a behavior that will cause its subject to act under impulse, affecting their rational decision-making. Sandy—like everyone else—is under no obligation to hurt or surpass her boundaries for the pleasure of her peers. Such a critique will only reinforce an unhealthy understanding of intimate and social activities, shaming those uncomfortable with the status quo. This is particularly problematic when we realize the antithesis to the “good girl” faces the exact same problem.

Indeed, on the other side of the binary, the “bad girl” is characterized by confidence, rebellion, and sexual prowess. She uses what she can, whether it be her beauty or wiles, to obtain her objective.

Phyllis, the assumed villainess of Double Indemnity, is a classic example of a “bad girl”. Phyllis is cunning, charming, and sharp, all in ways that benefit herself. Her role in the film is both the love interest and antagonist: she and the main character, Walter, with whom she is involved in an affair, eventually collude to murder her husband. However, when Walter realizes she is using his desire for her to take advantage of his job, he has two opposite reactions, both of which speak of the underlying misogyny and contradiction within this trope.

As he sits in his car, prepared to take revenge on Phyllis, he asks, “Who could have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?” While her deceit incites a murderous vengeance within him, he finds that her sexual appeal and mastery of people only add to her attractiveness.

The most hateful trait of this archetype is its most desired. It is critiqued by the very ones who demand it—a self-perpetuating cycle feeding off a hypocritical want. It is responsible for this archetype’s constant prevalence in every era of film.

But let’s take into account the previous critiques of the “good girl” and “bad girl” tropes. Within these two opposite tropes, neither of their physical nor sexual boundaries are respected. Both are either questioned or criminalized. It seems that no matter a woman’s boundaries with her body, somebody will have something negative to say about their decisions; any and every amount of bodily autonomy is not acknowledged, even though no one owns their body except for themselves.

The Double Standard

Any character who fits the “bad girl” trope is also painted in an unusual villainy, a distinct marker of the double standard between the criminal acts of men and women. Walter and Phyllis are both incentivized by selfish motives when they work together to kill her husband. Phyllis’s role in the crime is punished with the shot of Walter’s gun. Walter, on the other hand, is portrayed as a victim of Phllyis’ manipulation and beauty. Despite the equal severity of their roles in the crime, she gets the brunt of the blame, but Walter is said to be ‘innocent’ even as he has her blood running on his hands. The difference between their fates spells out the misogynistic disparity within this trope as it portrays sinister women as inherently more deserving of punishment than sinister men.

The Collective Issue

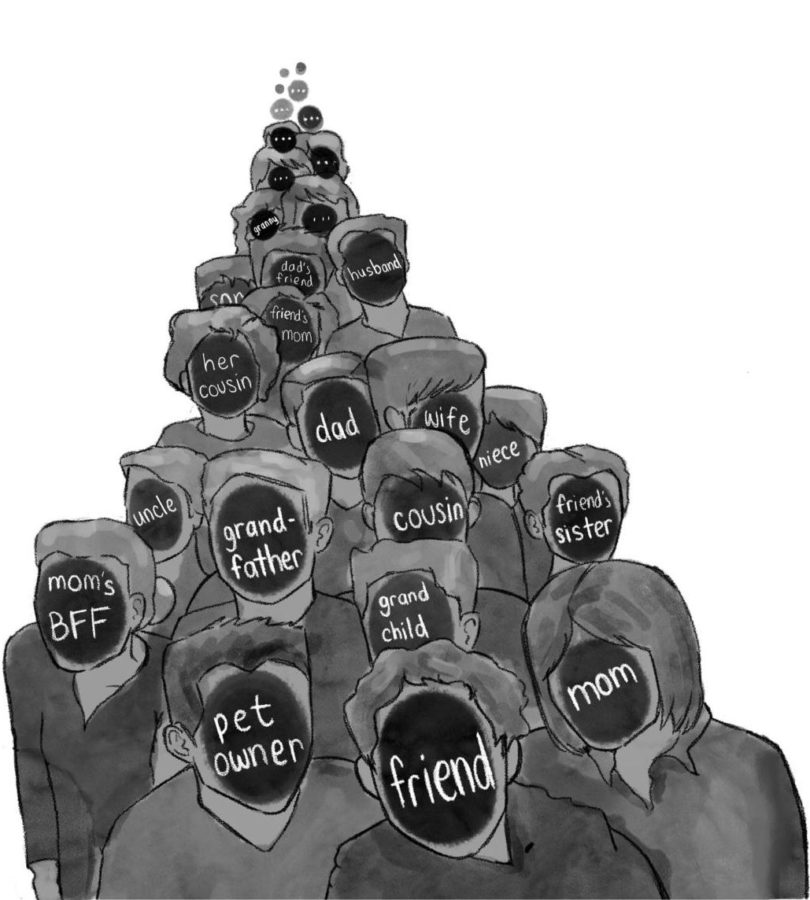

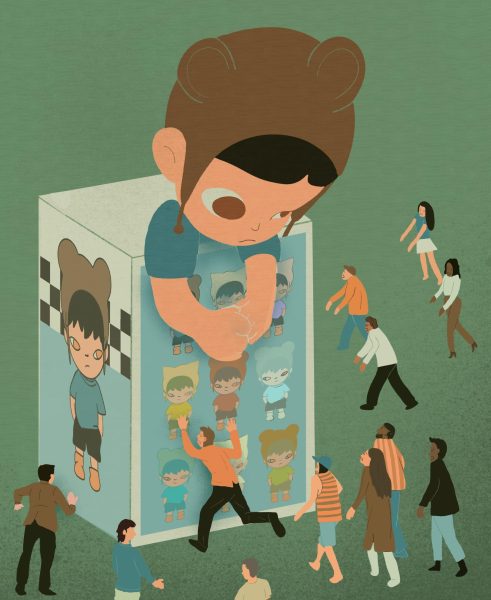

The “good girl” and “bad girl” are individually problematic, but together they represent a larger issue: the “Madonna-Whore Complex” (not to be affiliated with the artist “Madonna”). Freud—perhaps one of the most renowned psychologists of all time—coined this term when he realized the common root of relationship problems in his cisgender and heterosexual male patients: they would misunderstand and characterize their wives into one of two categories. Of course, those two types are “The Madonna” and “The Whore” archetypes, which correspond to the “good girl” and the “bad girl”, respectively. This meant they would match one of the two tropes to their lovers, and with it, its corresponding traits. Accordingly, they would completely disregard all the traits of the trope that their partners were less like.

The difference in the perceptions of the two is reflected in a trope of its own: the “good girl gone bad”. We see it in cult favorites such as Grease, Jennifer’s Body, Gone Girl, and more. As the name suggests, the archetype refers to a character who is initially a “good girl” turned “bad girl”. Sometimes, this awakening occurs after a traumatic experience. Notice that there exists a constant, bold disparity between the character before and after they have undergone a change, and that it is always contrasted as two separate entities. Often, when compared to her initial personality, the “Good Girl Gone Bad” responds with “who?” or says something along the lines of “she’s dead”, cementing the mutual exclusivity between the two personas.

This dilutes the importance of women’s individualities and rejects intersectionalities between the two tropes. Women come in all variations, all personalities, and definitely cannot fit into two cookie-cutter molds. It limits the growth and understanding of other genders to women, and women to themselves. Can they not be loving and promiscuous? Modest and rebellious? Kind and independent? Is that so wrong? After all, a balance is always ideal.

Women as depicted on screen are in dire need of improvement. First of all, we need better portrayals of the “good” and “bad” girl tropes, depicted without any unjust villainization or pressure to adjust their sexual and social boundaries; second, realistic characters who are neither—or both—of the tropes; examples that truly explore the nuances, complexities, and conflicts of these two tropes. This is how we can challenge the damages of the “good” and “bad girl”. We need to diversify this binary in order to minimize harm and misogyny toward women.

Alexandra, or as her friends call her, Alexa, had a very rocky start in journalism. She struggled and made many mistakes, always dramatic but never drastic,...

Staying awake late into the night at the expense of sleep, Diego has always had a great passion for conveying his interpretations and visions through art....