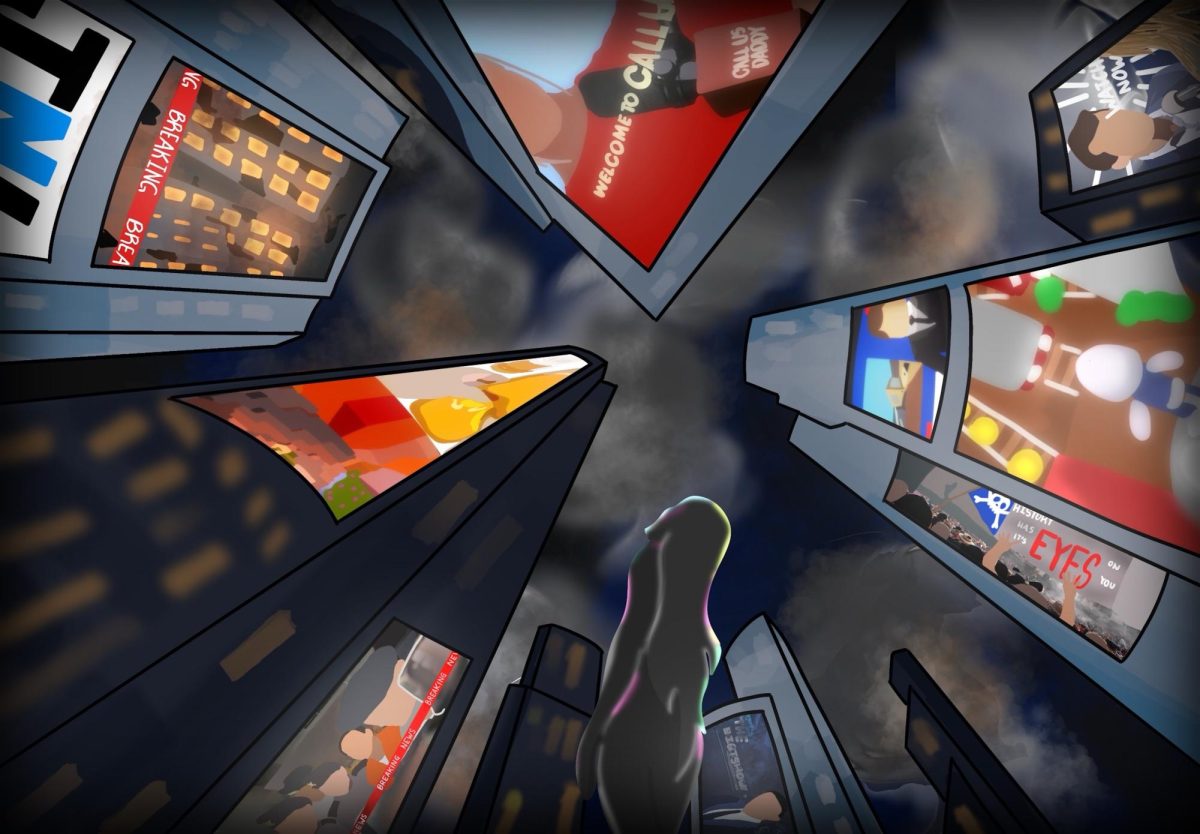

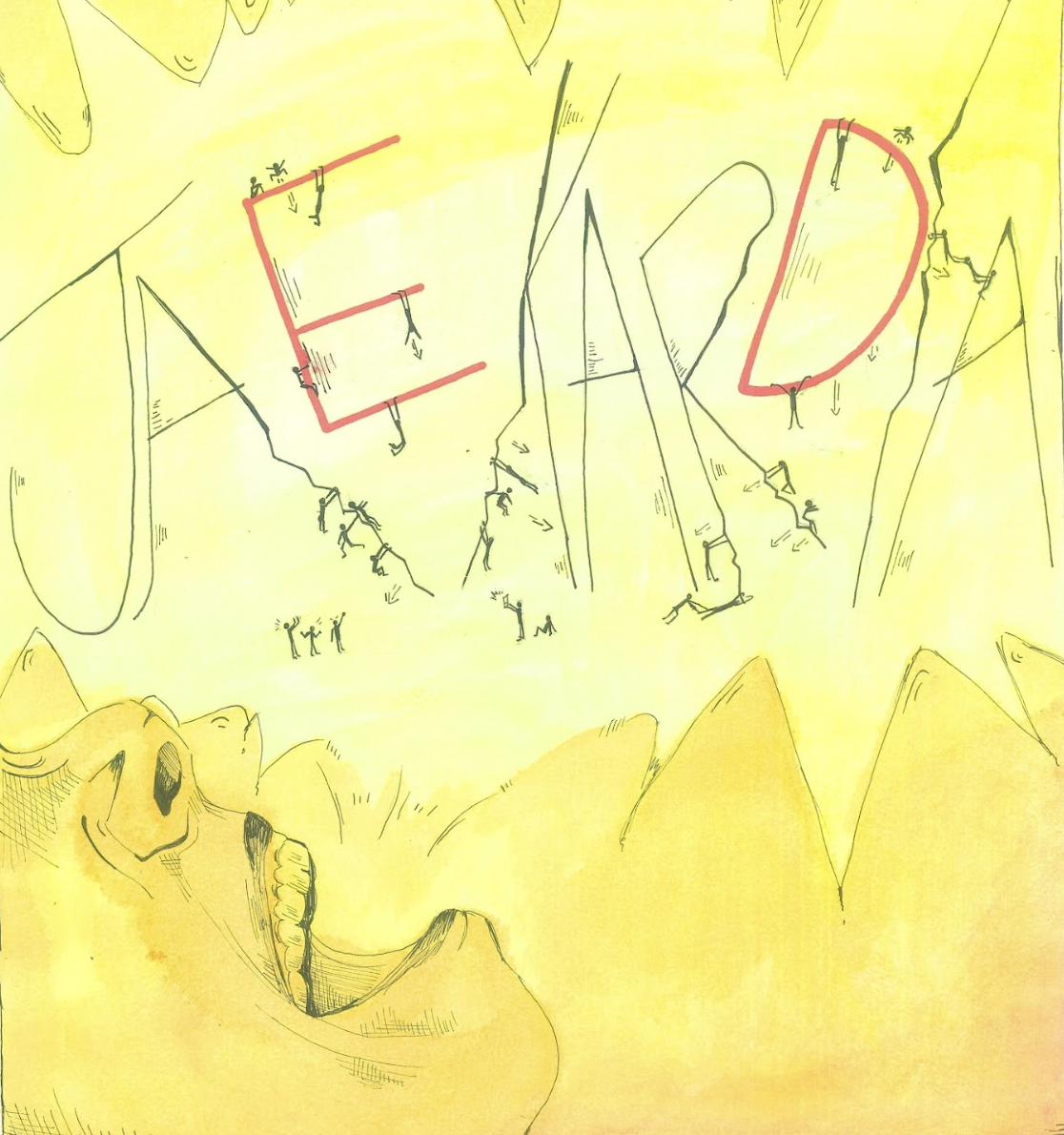

Imagine this familiar scenario: You are doom-scrolling through TikTok or Instagram and see posts about a devastating wildfire, a political scandal, or a war-torn city—a catastrophe unfolding in real time. Swipe. Suddenly, the latest dance craze, an edit of a celebrity, or a gossip podcast. The juxtaposition is absurd—but admit it, you barely even flinch anymore.

Tragedy and triviality constantly sitting side by side have culminated in our feeds, essentially leaving us to take both disaster and distraction in the same breath. That uneasy balance we experience every day has a name: Hypernormalization—when dysfunction appears so often that at a certain point it stops feeling extraordinary and starts passing as normal.

Why does hypernormalization matter? Events that should be disturbingly shocking now appear sandwiched in between memes and scandals, and we scroll on. Once-in-a-lifetime crises appear on our feed weekly, yet they barely grab our attention anymore.

Hypernormalization may only sound like an abstract term, but it might just be the single largest issue our society is unknowingly facing today, because if society forgets how to feel alarmed, it also forgets how to demand change.

Origins

The term hypernormalization was first coined by scholar Alexei Yurchak in 2005 to describe life in the Soviet Union. In that context, everyone knew the system was failing, but people carried on with “normal” life, pretending all was well because they could not envision an alternative. If we transpose this to the media-saturated society we are engulfed in today, hypernormalization describes a collective state of denial and acceptance: people see that systems and institutions are broken, yet we go through the motions of normal life despite the dysfunction.

We do this, as Yurchak noted, while carrying a “heavy load of fear, dread, denial and dissociation” about the current state of the world. In other words, there is a disconnect between reality and what we are willing or able to acknowledge.

Social Media Relevance

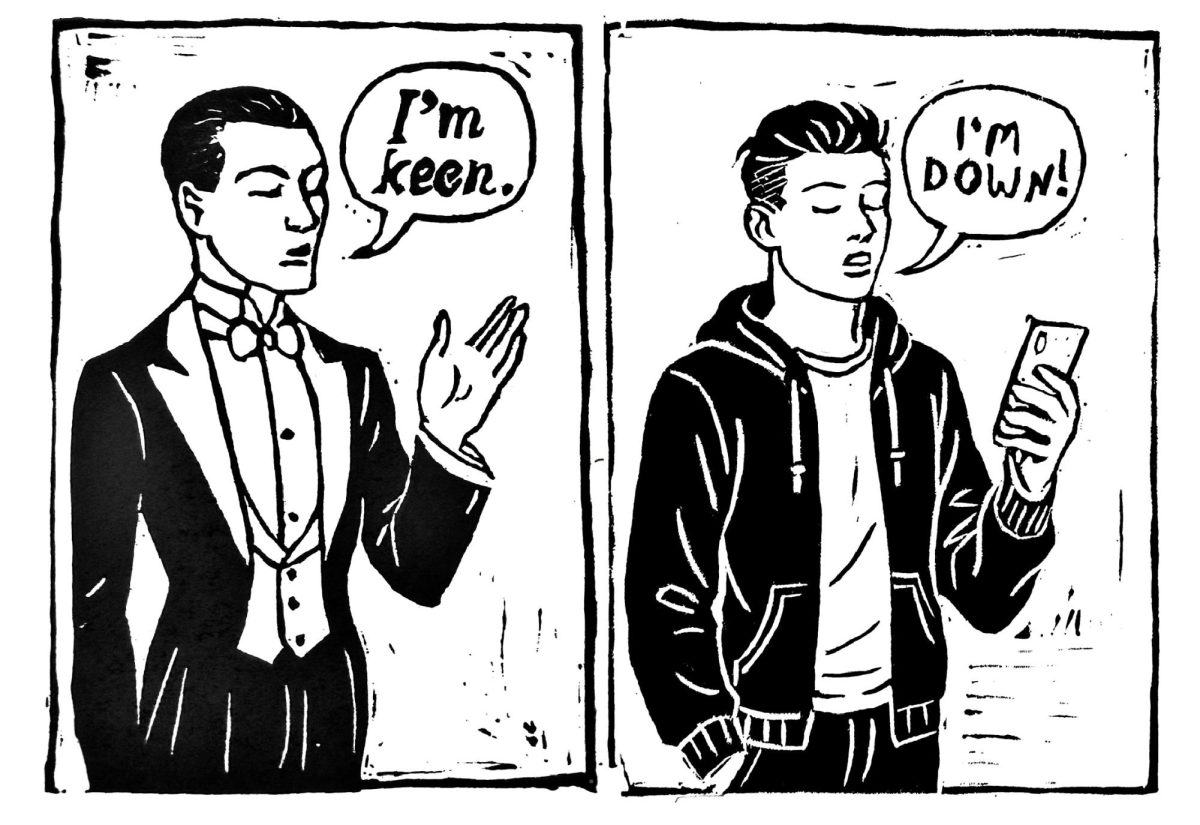

There has never been an age when information is this readily accessible, where one can switch from a video of a friend’s viral dance to devastating news in the span of a second. Social media has now become a shared space where personal interests and hobbies are intertwined with news.

For the younger generation, the effects of hypernormalization are amplified by these algorithms.

According to a study by Ofcom, 80% of 16-24-year-olds are more likely to get their news from online sources and individual creators rather than established news outlets. While this accessibility opens up opportunities to become engaged, it can also cause an overload of information and, in turn, hypernormalization. Online, these issues are presented in short-form content, which often only comprise a brief summary of events without much depth. Instead, this type of media is packaged with striking visuals, titles, and clips that prioritize attracting as many viewers as possible. Social media can provide countless sources of information, as well as the unique opportunity to directly hear from someone experiencing a situation firsthand. However, the fast-paced nature of the algorithm traps users in a cycle of endless scrolling that ultimately leaves them feeling fatigued by the exposure.

In a survey conducted on the JIS high school student body, most respondents said they frequently encountered serious topics online, with only 6% saying they had never been exposed to global issues when scrolling.

One student expressed how, “when new tragedies surface almost daily, audiences feel unable to process them all, and therefore choose to disengage emotionally.” What this disengagement and loss of urgency does to young minds can be detrimental as they mature.

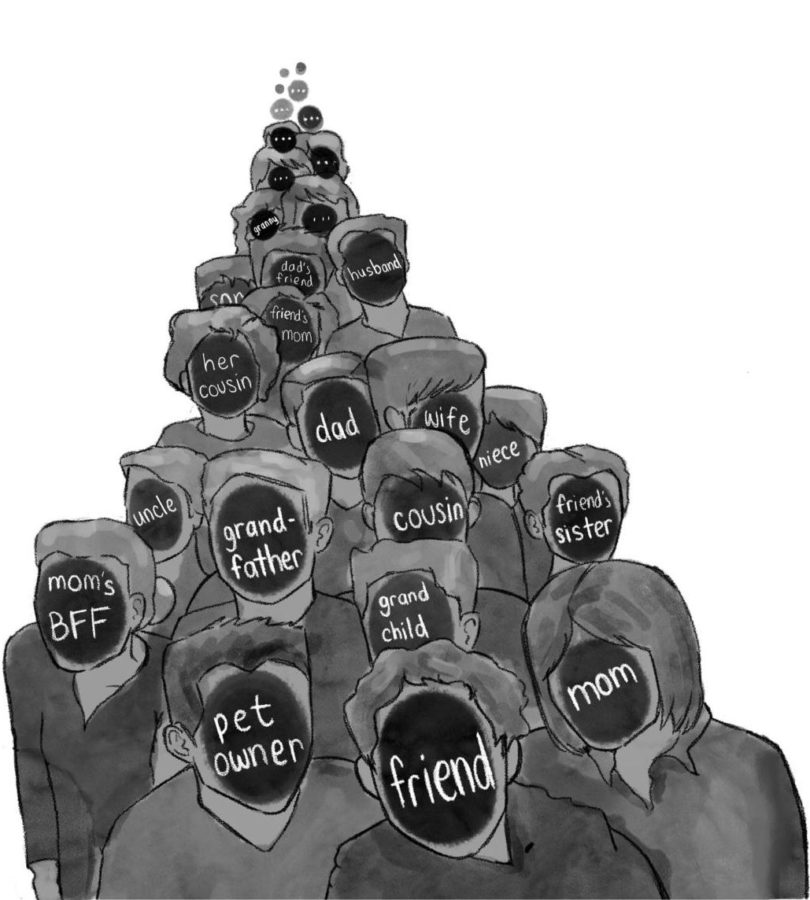

In many cases, that disengagement does not necessarily equate to silence but can morph into a more performative response. For example, social media has offered a leeway for young people to sit with their discomfort: reposting. An upcoming protest against the government? Repost. The death of a podcaster for their political beliefs? Repost. A famine emerging in war-torn countries? Repost. Sharing posts feels like participation, but too often it creates the illusion of impact without the substance of action.

“I feel like people only repost things about the news just because, why not?” a student commented. “[However], there’s no real meaning behind the actions.”

While reposting is not entirely meaningless (it spreads awareness) when it comes to the main form of “activism,” it essentially acts as a pressure valve when sitting with the discomfort. In the landscape of hypernormalization, where apathy already runs high, performative activism can blur the line between genuine resistance and passive scrolling as reposting largely leaves the systems that need challenging untouched.

The Broader Implications

Furthermore, the larger implication of hypernormalization lies in how it dulls our moral alarm bells. When we scroll past starving families or forms of political oppression, like it is just another item on your feed, we risk losing our sense of empathy and urgency. Over 70% of survey respondents at JIS expressed that the constant exposure to serious issues on social media has made viewers desensitized to serious topics. When the public becomes overly desensitized, outrage fades into resignation as problems are still recognized, but are considered inevitable rather than urgent.

One student expressed, “With the permeation of social media and all the negative news we see online, each additional tragedy just feels less important.” Users are stuck in a cycle where each new crisis competes for attention with the last, until even the most shocking events feel like background noise. This constant layering of tragedy flattens emotional response, conditioning people to accept dysfunction as part of everyday life.

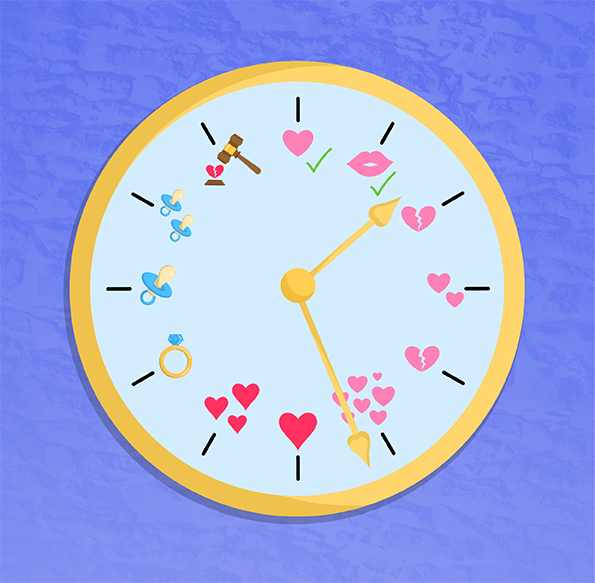

This links to the Overton Window—the range of ideas the public considers acceptable at a given time. Hypernormalization is what happens when the window shifts so dramatically that even dire situations become the backdrop of life. Events that once would have sparked outrage instead elicit a shrug because it has become normal. For example, decades ago, a major corruption scandal might have dominated headlines and shocked the public; today, new reports of political graft or bribery are often met with indifference. To many, while they may not internally approve of it, simply say, “Well, that’s politics,” as if corruption is an inevitable feature of governance. This normalization of dysfunction is dangerous, as the more we accept the unacceptable as “how things are,” the less we uphold the principles of truth and accountability. If media-induced desensitization causes us to disengage, then who will advocate for what’s right?

As Adrieene Matei, a writer at The Guardian, puts it, “What makes dysfunction so dangerous is that we might simply learn to live with it.” The public becomes collectively apathetic where injustice and suffering continue to go unchallenged. Those in power—whether politicians, corporations, or full governments—face less pushback, and they can continue to exploit these institutions for their own benefit.

We have seen hints of this in recent years: repeated assaults on democratic norms or human rights worldwide might provoke momentary outrage online, but then everyone moves on to the next story, and for the most part, meaningful action is put on the back burner. People move on with their lives, and the only ounce of acknowledgement these issues earn is in the form of “Well, what can we do about it anyway?”

Moving Forward

In reality, there are tangible steps that young people can take to reduce the effects of hypernormalization.

One of them is separating their spaces for entertainment and information. For instance, instead of relying on TikTok or Instagram as the only news source, students can choose to use these platforms primarily as social networks and for lighter content, but turn to established news outlets for updates on global issues.

If traditional news articles are unappealing, plenty of reputable news sources now produce podcasts where journalists discuss global topics in daily episodes through an accessible and conversational manner. They are easy to put on during the commute to school or in any free time as a replacement for doom-scrolling.

By consciously deciding where to seek entertainment versus information, we preserve our empathy and urgency while keeping ourselves informed enough to act against injustices.

It is equally important to avoid slipping into performative activism. Reposting on platforms could spread information, but they should not replace meaningful engagement. Users must remind themselves that sharing a post is not the same as addressing the problem, as real change requires more than signaling support. As the Overton Window already minimizes the severity of many issues, if tragedies are treated as just numerical values on a feed, users tend to forget that these are the lived moments of actual individuals. Thus, by contextualizing news as lived realities rather than statistics, it can switch apathy to empathy.

Recent events in Myanmar illustrate this difference vividly, with students and ordinary citizens who took to the streets—risking arrest and violence—in demand of democracy. Their actions show what genuine activism looks like, something impossible to confuse with a double-tap like or a repost.

If we allow tragedy to blur into the background, we risk falling into a state of complete apathy. Recognizing hypernormalization is the starting point for resisting it, but recognition alone is not enough. It takes choosing not to fall victim to becoming simply an observer in this fast-moving and sensationalized digital landscape. After all, if everything starts to feel normal, then nothing will ever change.