In August of this year, a TikTok street interview went viral when a young Indonesian woman pronounced the capital city as “Jek-ar-dah”–a more Westernized pronunciation–instead of the local “Jak-ar-ta”. The clip quickly drew thousands of comments, many expressing confusion or annoyance. One comment read: “If you are a Native American, you might pronounce Jakarta differently. However, since both of you are Indonesian, it may be better to say ‘Jak-ar-ta’ directly to be more accepted.” At first glance, the debate seems just a matter of a single syllable: “ta” versus “dah”. But beneath the surface, this controversy exposes deeper fractures in language, identity, and belonging—ones that resonate strongly within international schools like JIS.

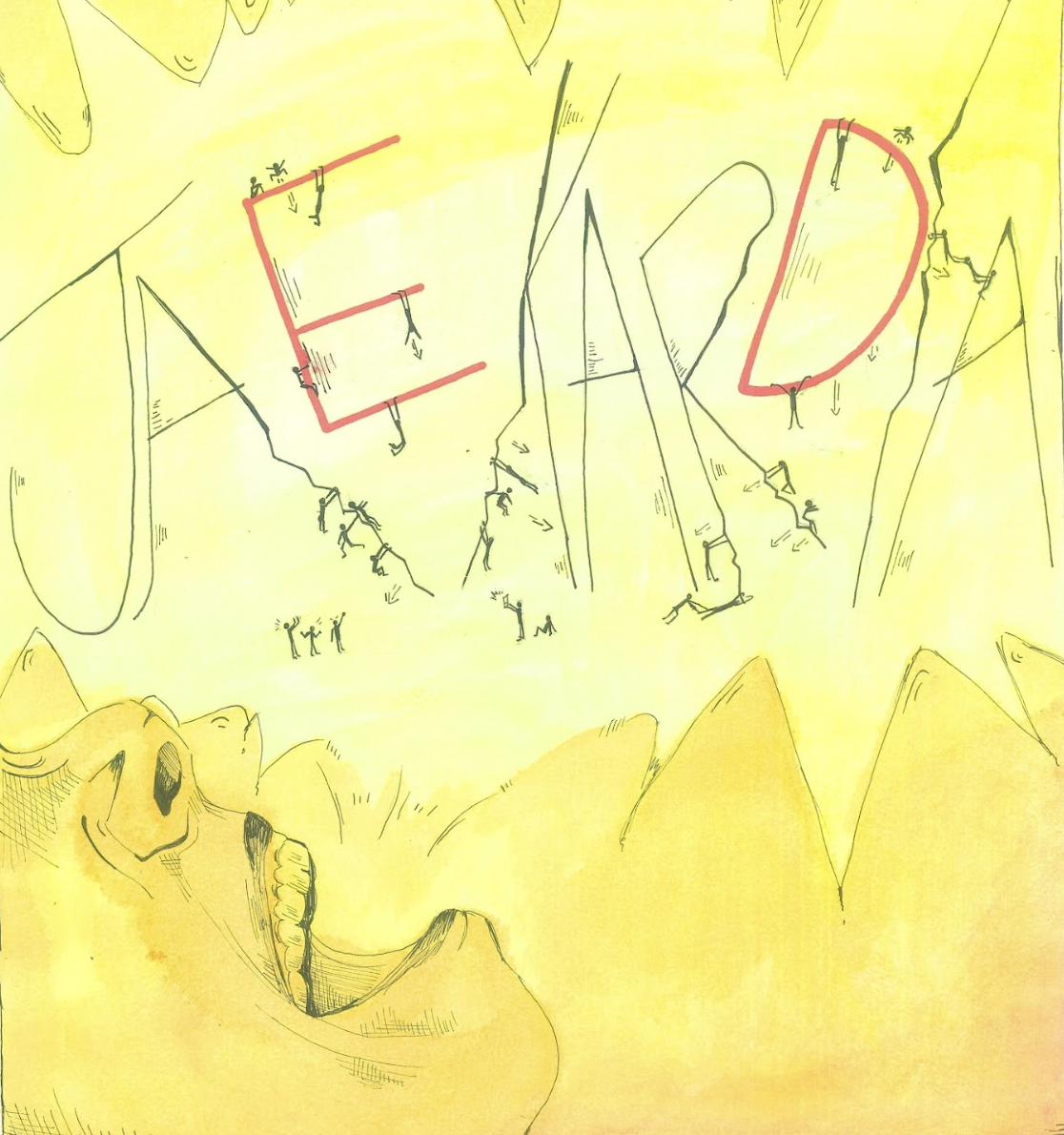

Accent Policing

The backlash against the pronunciation highlights a broader phenomenon: accent policing, or the act of judging how ‘authentic’ someone sounds when they speak. Indonesians who speak English with a Western accent–or mix English with Bahasa Indonesia–are often accused of being “sok bule”, a phrase suggesting they are acting as if they are white and feel superior because of it.

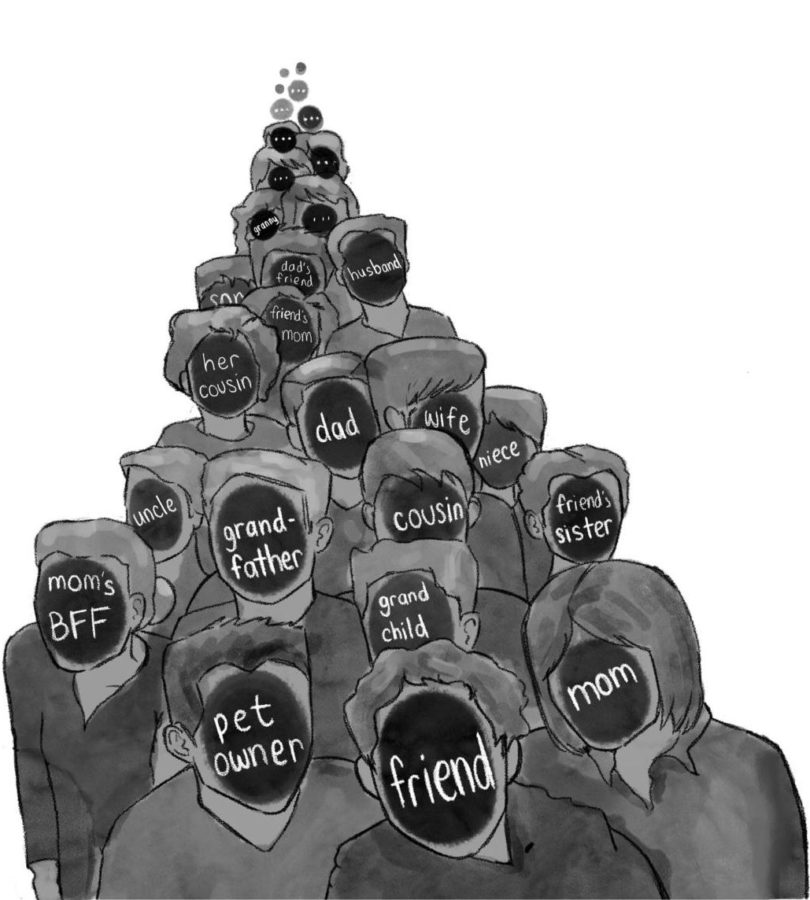

At JIS, this type of judgement is often reflected in how confident students feel when speaking Indonesian with different people. Nearly 85% of Indonesian students feel comfortable speaking Indonesian with immediate family, where encouragement and familiarity are common. Confidence dropped to around 70% with friends, who are often supportive but may not share the same language background. With extended family, comfort levels decreased further to 65%.

This gap may reflect generational differences in expectations and norms. Older relatives often value more traditional or formal speaking of Indonesian, while younger students are shaped by exposure to international media and schooling. The lowest confidence was with strangers at just under 60%, where judgments are often harsher and awareness of a student’s global upbringing is limited.

“With Indonesia specifically, culture is a very big thread and language is one of those links that connect all of us,” Indonesian 10th grade student Kianu explained. “Just the effort of trying to speak the language already gives me a decent amount of confidence”. Still, he admits he is not yet proficient enough to feel fully confident speaking Indonesian with everyone.

Like many other students, he has faced judgement, usually from those closest to him: “I’ve definitely been criticized for my Indonesian being too informal from people I know, more so from family since my friends also don’t speak perfect Indonesian.”

This criticism can feel discouraging. Accents and pronunciations are sometimes judged according to personal notions of what “authentic” Indonesian should sound like, even when students are making genuine efforts to connect through language.

Navigating Between Worlds

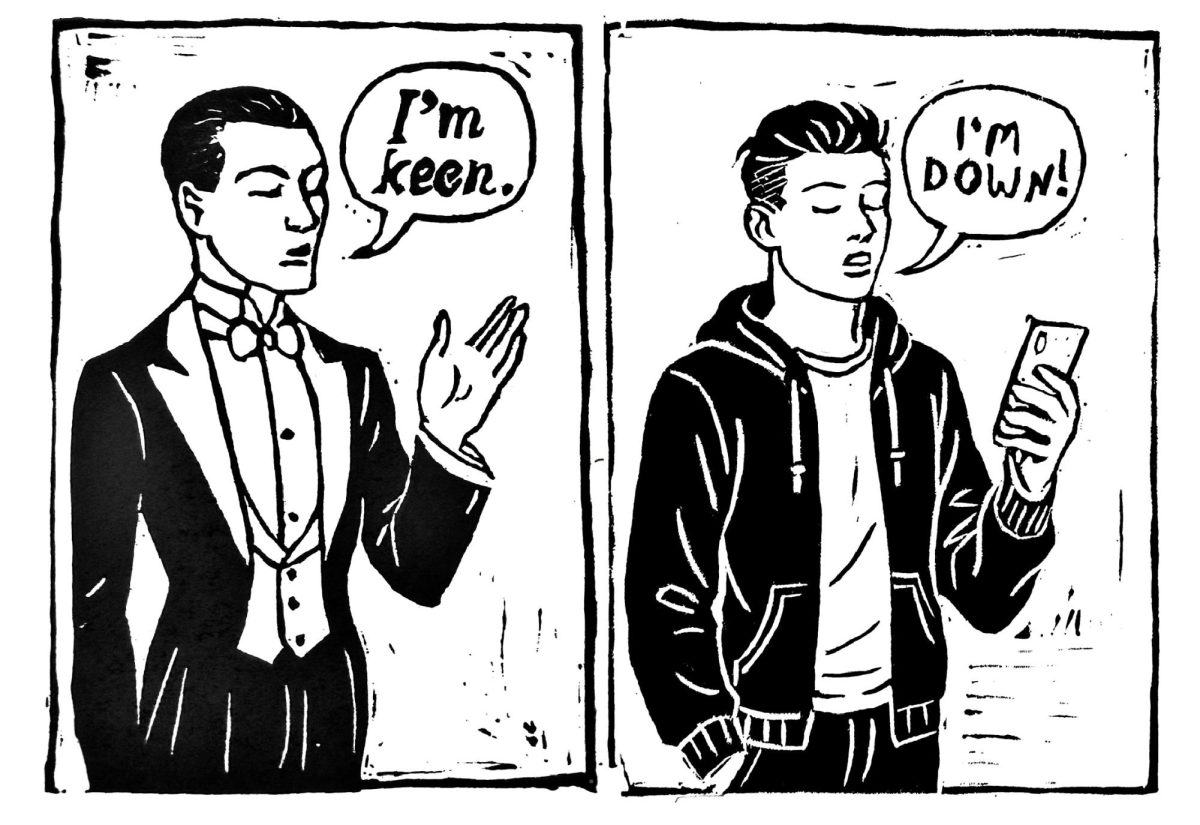

In international schools especially, code-switching–the act of changing languages, tones, or accents depending on the audience–is second nature. With foreign teachers, students may adopt a “more Western” intonation. With local teachers, they may emphasize a “more Indonesian” tone.

Many students describe this as less a skill and more a habit or necessity. Speaking “too local” can feel out of place, while speaking “too Western” can feel like betraying one’s heritage. Over time, this juggling produces a hybrid accent, in Jakarta often called the Jakarta Selatan (South Jakarta), or Jaksel accent, where Indonesian is spoken with English intonation and rhythm. Since it is often associated with South Jakarta’s international schools and upper class youth, the accent is seen as a marker of social class and privilege. While hybrid accents signal bilingual skill, it can also make students targets for teasing or criticism—teasing that often reflects deep social and cultural stereotypes about identity.

Teacher’s Perspectives

Teachers at JIS have seen how these judgements often stem from broader perceptions. One Indonesian teacher, Pak Jon, explained: “The Jaksel accent is easier to make fun of, it’s kind of like punching up because many Indonesians see it as a marker of social standing or economic class…it’s like trying to make fun of people who they think are more powerful than they are”

He recalled being the only international school student in his Indonesian friend group at university, where he was teased for sounding “Jaksel”. Rather than suppressing his identity, the experience motivated him to study Indonesian history in university, hoping it would connect him more deeply to his culture.

Pak Jon emphasized that international schools must recognize the local context in which they operate. Since schools like JIS participate in global competitions like Interscholastic Association of Southeast Asian Schools (IASAS), he noted how easy it is to forget the physical and cultural environment of Indonesia. He encourages both Indonesian and non-Indonesian students to take courses like Indonesian studies, noting that the JIS motto, “learn in Indonesia to be best for the world,” demonstrates the school’s commitment to engaging with this context.

Ibu Dossy, another Indonesian teacher, echoed this sentiment. She admitted that her own child, who attends an international school, has been criticized by relatives for sounding “foreign.”

“Many Indonesians are traditional and have limited exposure to the outside world. If someone has very limited experience, you cannot do anything,” Ibu Dossy explained. Because international school students like her child have had greater access to different cultures, she tells them: “You have to be tolerant. Because you are not limited–you’ve met people, traveled, and seen the world–you have to understand them.”

Holding on to roots

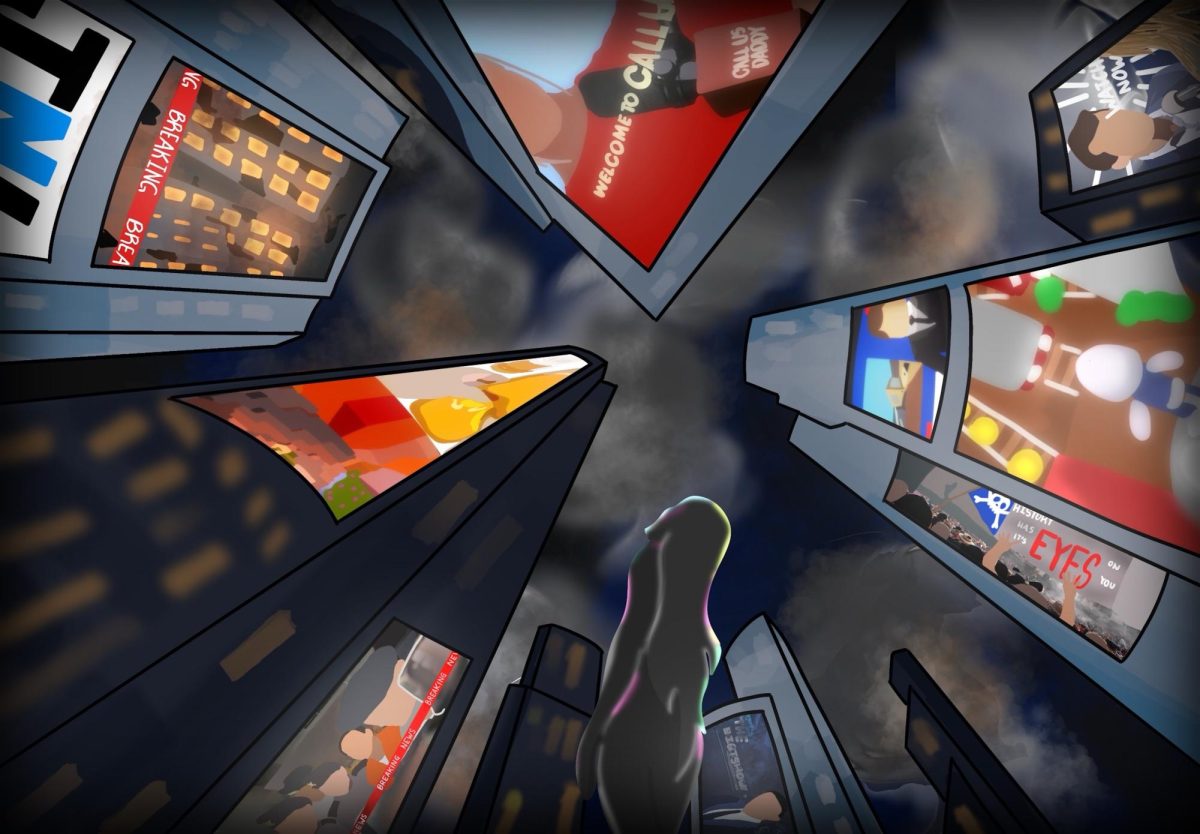

While the “Jek-ar-dah” debate is specific to Indonesia, it reflects a wider issue: being judged for how one speaks. For many bilingual, third culture, and international school students, this can create tension between belonging and authenticity. Some describe moments of being told they sound “too foreign” in one space and “too local” in another.

Still, committing to language is what keeps identity intact and ties us to our cultural roots. One student reflected: “Especially going to JIS, it’s oftentimes hard to stay grounded with your culture. There’s a saying in Indonesia ‘Seperti kacang lupa kulitnya’, like a peanut forgetting it’s shell. Indonesian is what keeps my peanut shell.”

In the end, navigating multiple identities is what makes international communities like JIS so rich. By integrating both global and local perspectives, students can turn that complexity into a strength. Accents carry more than just sounds—they hold stories of movement and belonging, stories that should be embraced.