At the age of twelve, pre-teens once spent afternoons doodling in notebooks, trading friendship bracelets, and laughing at inside jokes. Today, many are speaking in the language of social media influencers, curating Instagram feeds, and contouring their faces. Sometime in the last decade, the pace of middle school sped up—what once was a stage of authentic discovery has become a public square of pressured performance.

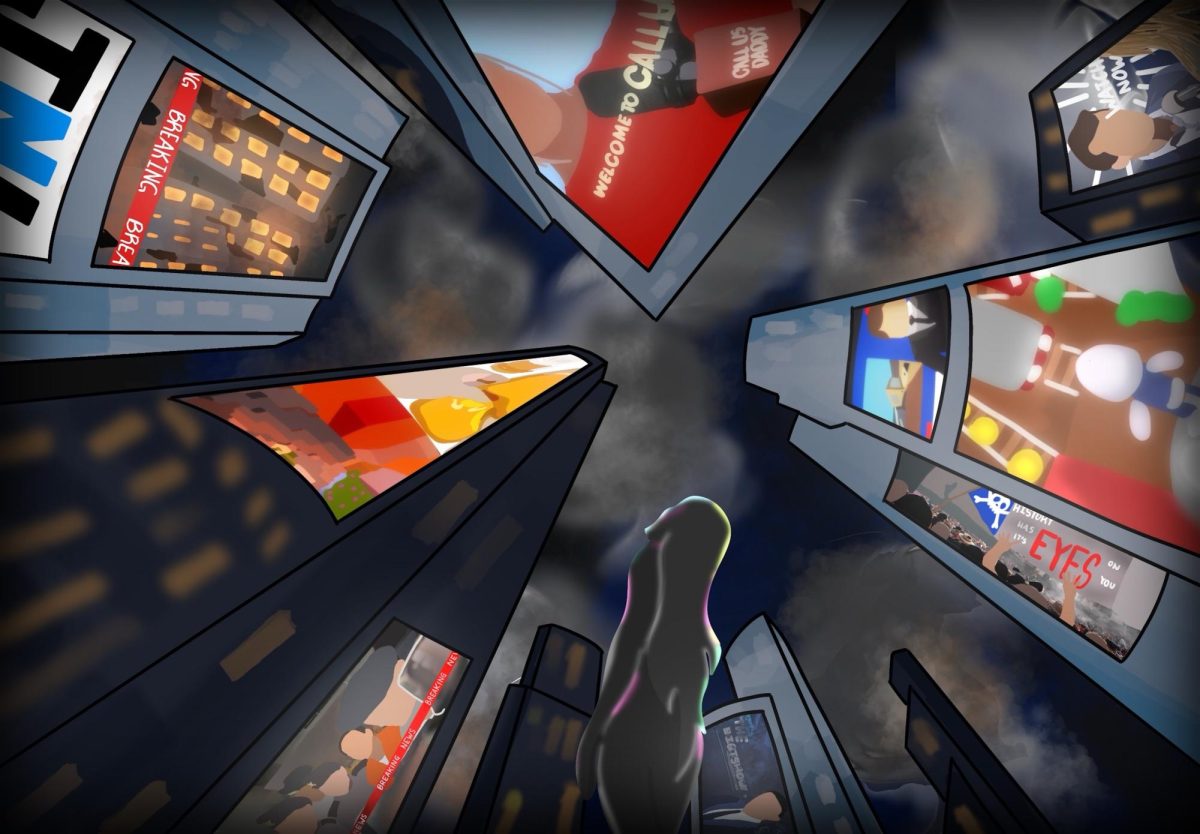

The Social Media Mirror

It is tempting to point the finger at TikTok, Instagram, or Snapchat—and to be fair, social media definitely plays a significant role. The U.S. Surgeon General warns that heavy use may alter brain regions tied to emotional regulation and impulse control. And the Reach Institute reports that middle schoolers who spend more than three hours a day online are twice as likely to experience symptoms of depression and anxiety.

By design, these platforms intensify exposure. Pre-teens scroll through “get ready with me” videos, beauty tutorials, and relationship content for older teens, facilitating constant influence and co-comparison.

As middle school counselor, Ms. Burke explained, “When students watch a couple of videos, [the social media] algorithm shifts, narrowing down their interests at exactly the time when they do not yet know what their passions really are. It is a tunnel vision effect that looks like exploration but actually is not.”

Pushed Ahead

But the problem extends beyond algorithmic rabbit holes. Middle schoolers live in a culture where looking and acting older is rewarded. Parents and schools often prize “mature” behavior—responsibility, independence, and leadership—valuable in theory, but can push kids away from the messier parts of growing up.

As school psychologist Ms. de Swardt observed, “In a competitive environment, parents and schools often set expectations for students to be older than they are. [That pressure], if sustained, can lead to burnout.”

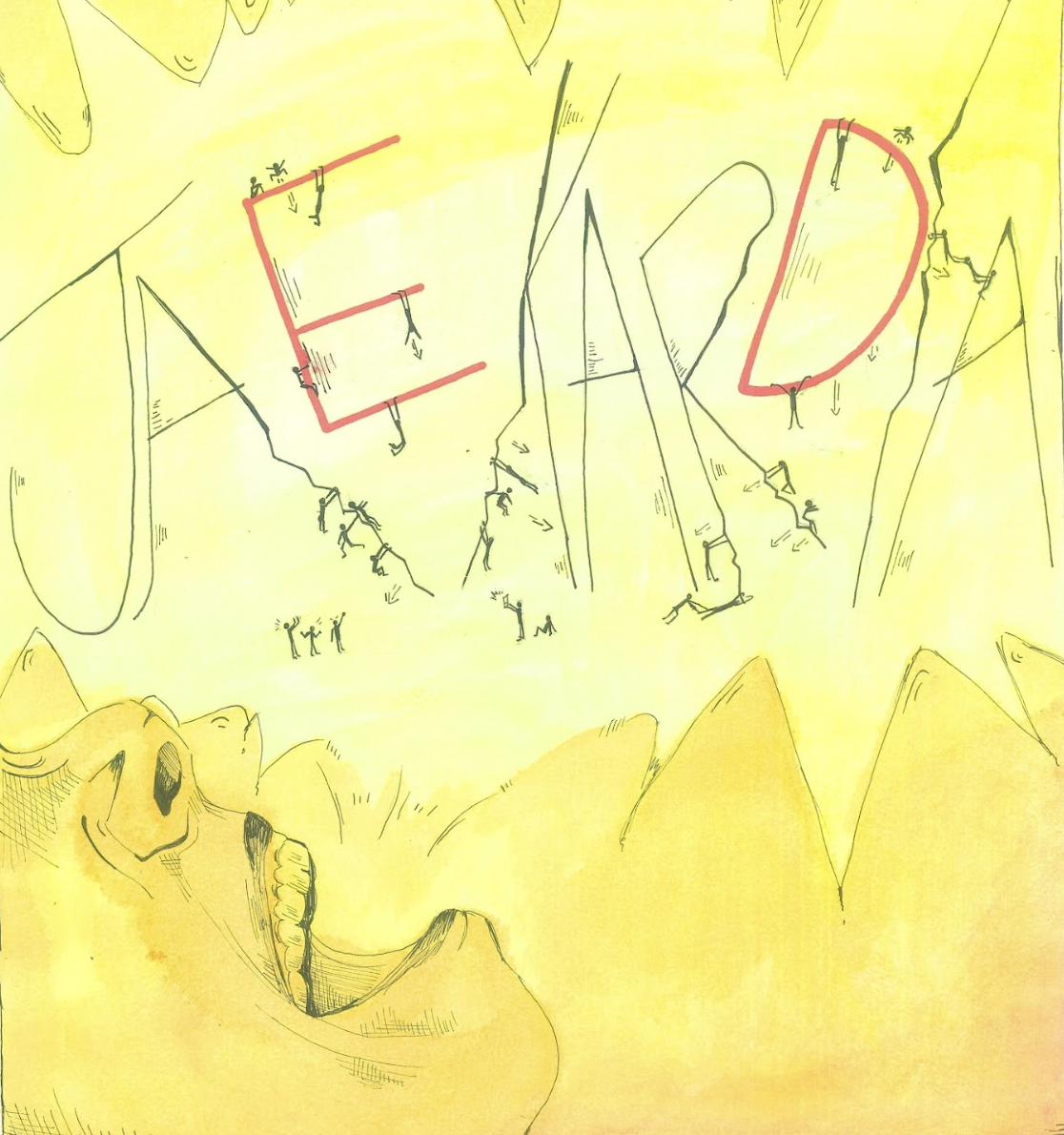

Skipping Stages

Developmental psychology reminds us that childhood is not simply a waiting room for adolescence, it is a critical stage in itself. Play, imagination, and unstructured time are practice grounds for empathy, resilience, and problem-solving. When middle schoolers are hurried past these stages, they do not simply “grow up faster.” Instead, they miss essential chances to develop skills that are difficult to recover.

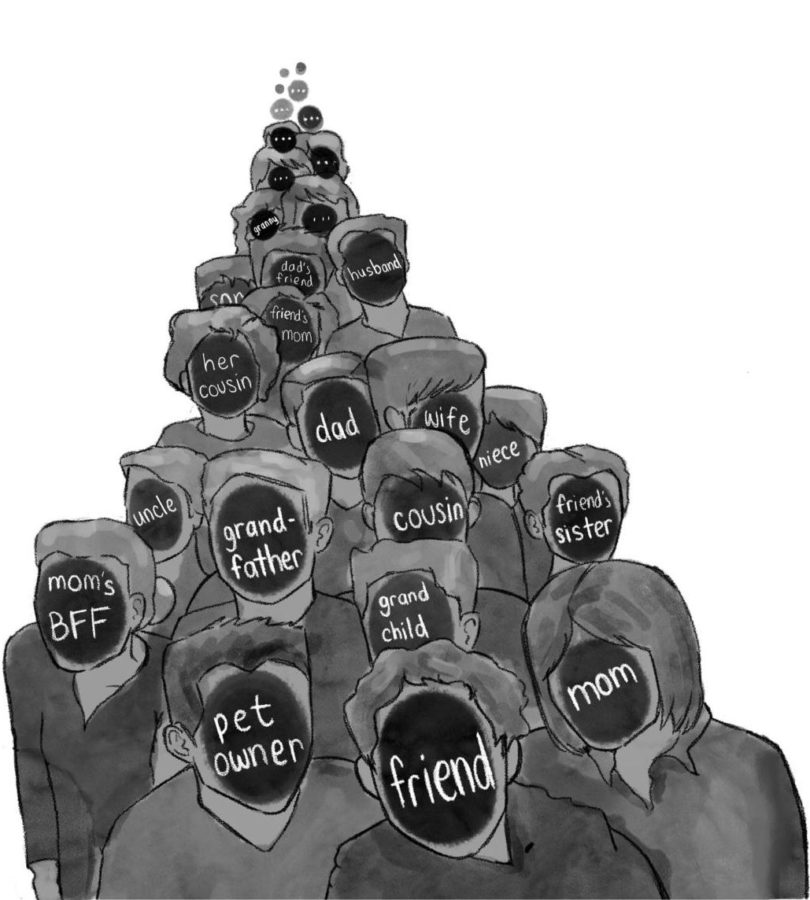

At JIS, middle school is often described as a time to explore passions, take risks, and discover who you are. Yet, for many students, that exploration is being outsourced. Instead of asking, “What do I enjoy?” the question becomes, “What will others approve of?”

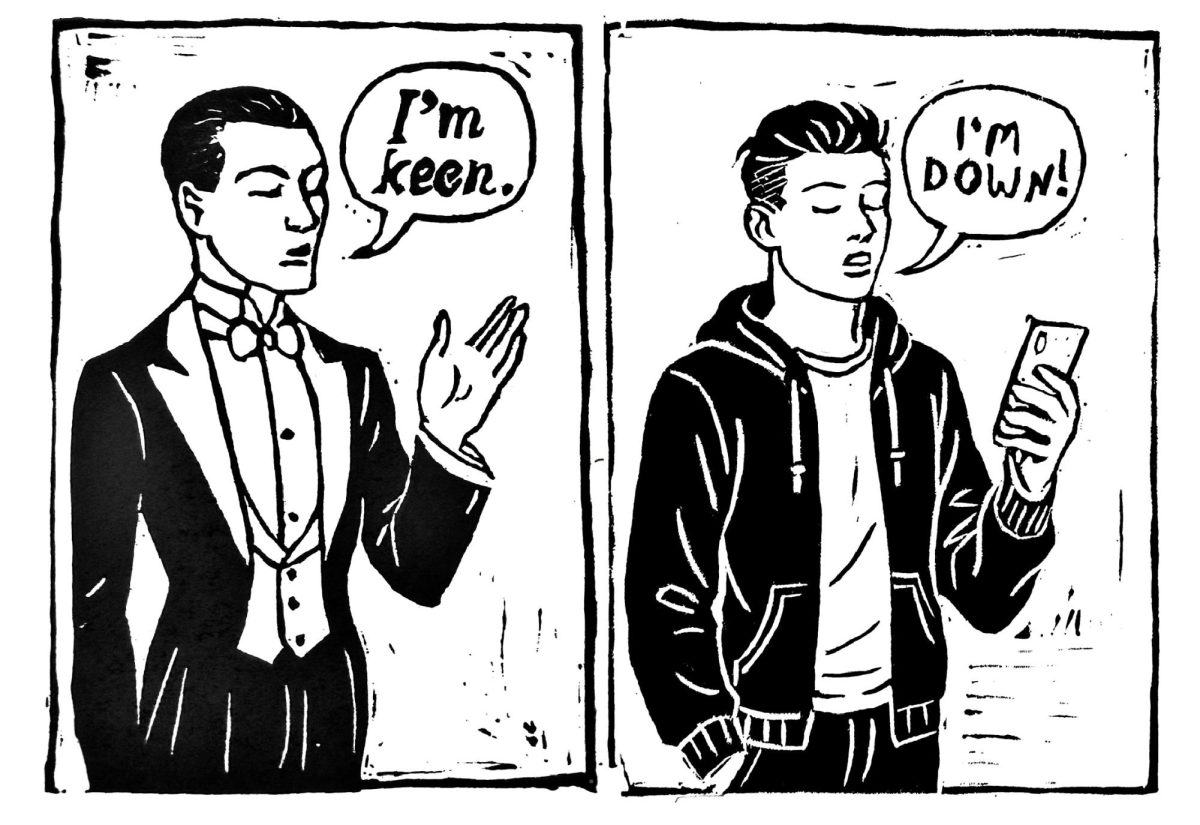

Pretend Maturity

This is where we see the divide between genuine growth and what might be called “pretend maturity.” Genuine growth is messy: trying out debate even when your voice shakes, sketching ideas that might never make it past the page, joining a sport you are terrible at, or admitting you do not know who you are yet. Pretend maturity, on the other hand, is polished: dressing older, adopting slang, curating a persona—imitating adulthood long before you are ready for it.

“It is a double-edged sword,” Ms. Burke reflected. “There is so much information out there for students to learn from, but when they are only exposed to certain content, they can feel trapped. ”

Costs That Carry Over

When middle school rushes forward too quickly, the consequences do not fade with age. Instead, they surface later as anxiety, perfectionism, a faulty sense of identity, or a combination of all three. High school counselors often see students who seem mature on the surface but struggle deeply with self-esteem.

“Always comparing themselves to unrealistic standards—especially on Instagram—leaves young people vulnerable,” Ms. de Swardt said. The irony is that while students are trying to look mature, heavy screen use and social pressures actually leave them less able to tolerate discomfort, regulate themselves, or think independently—all of which are central to real maturity.

Resilience is not built by prematurely taking on adult roles but by gradually stretching into challenges with the safety net of still being young. Without that net, mistakes feel catastrophic and adolescence becomes high-stakes theater.

Ms. Burke has seen this firsthand: “It is normal to feel awkward and uncomfortable in middle school. But when [students] feel they have to look or act a certain way, they do not get to practice that awkwardness, which is a part of discovering who they are.”

Who Feels It Most?

This pressure does not fall evenly. As Ms. de Swardt observed, girls often face it first, confined by beauty standards and early scrutiny over appearance. Boys, meanwhile, are propelled toward stoic indifference or unhealthy bulking trends.

Ms. Burke notes even subtle forms pressures “how students think they should act, long before they are aware of it.”

Allure magazine has dubbed this shift the rise of “Generation Beauty,” where self-presentation seeps into younger and

younger ages.

What We Are Losing

The bigger question is: what do we lose as a community when middle schoolers do not get to be middle schoolers? We lose relating when comparison replaces connection. We lose resourcefulness when imitation replaces imagination. We lose reflectiveness when external approval replaces genuine self-discovery. We lose resilience when trial-and-error is replaced by polished facades meant to avoid embarrassment.

And most of all, we lose joy. Not the curated kind, but the genuine, unfiltered, spontaneous joy of being fully present in the moment.

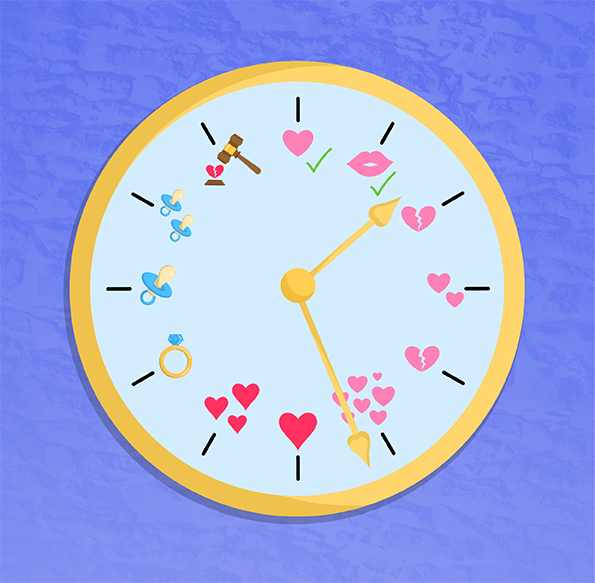

Slowing the Clock

So what can be done? We cannot roll back technology or pretend the digital world does not exist. But we can carve out intentional spaces where pre-teens are allowed—even encouraged—to slow down. Protecting time for play is not wasted potential but rather the soil where curiosity and passions can grow.

According to Ms. Burke, a healthy middle school experience is about “making choices, having room to make mistakes, and feeling safe doing it. That is where students find their voice and passions.”

At the JIS Middle School, the phone policy has been a game-changer: students place their phones in Yondr pouches at the start of the day, keeping them inaccessible until dismissal.

“I have seen more [students] just sitting together and talking without their phones, or even playing again,” Ms. de Swardt said. “That free time has been really healthy.”

Because childhood is not wasted time—it is the foundation. When children fast-forward through it, they build adolescence—and adulthood—on shaky ground.

The confidence of many pre-teens is admirable—the ability to navigate trends, adapt to new platforms, and speak with the intonation of someone older. But it also raises questions: are they getting the chance to be twelve, or are they sprinting toward versions of themselves meant for twenty? And truthfully, adults do not have a neat definition of “growing up” either. Watching middle schoolers blur the line between childhood and adolescence forces us to ask whether maturity is something to perform, or something we should allow to unfold.

Childhood is vanishing, and it is time to fight for it—not out of nostalgia but because a healthy adolescence and adulthood depend on it. The foundation is being eroded, and it is on all of us to hold the line: for parents, to protect space for play and curiosity; for high schoolers with younger siblings, to model patience and silliness instead of pressure; for teachers and communities, to honor growth that is unpolished as much as achievement that is polished. Because if we do not, the cost is not just to today’s middle schoolers, but to the kind of adults they will one day become.